The Rice That Never Reaches the People

Mauritius produces tons of rice each year—metaphorically speaking. When the harvest of GDP, taxes and public wealth gets divided, however, ordinary citizens receive just five grains on their plates. Politicians then take back three under banners of "austerity" or "subsidy reform." From the remaining two, they theatrically return half a grain at election time, demanding gratitude for this "generous gift" of the people's own produce.

Meanwhile, the warehouses stay full.

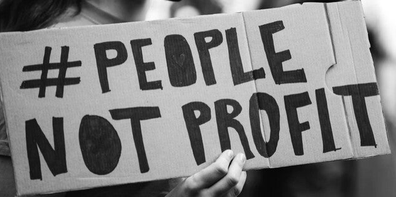

This metaphor captures the reality of Mauritius' political economy, where a small elite captures the bulk of national wealth while citizens are told to be grateful for crumbs. Far from the "African miracle" of international headlines, the Indian Ocean island nation has become a case study in how democratic institutions can mask systematic wealth extraction.

The hollow miracle

International observers have long praised Mauritius as a beacon of African democracy: stable elections, ethnic harmony, and steady growth since independence in 1968. The island ranks well on governance indices and maintains investment-grade credit ratings. Yet beneath this polished surface lies a different story.

Public debt has climbed above 80% of GDP, youth unemployment hovers around 25%, and a 2011 Truth and Justice Commission exposed entrenched patterns of colonial-era land dispossession that persist today. The IMF's latest Article IV consultation warns of "eroding institutional trust" and "risks to medium-term stability"—diplomatic language for a system under strain.

The problem is not growth but distribution. A handful of families still control the most fertile land and commanding economic heights. Sugar estates that once relied on slave labor now benefit from subsidies and preferential trade deals. Banking, textiles, and tourism remain concentrated among established business houses, many with roots in the colonial plantation economy.

The psychology of gratitude

Why do citizens accept this arrangement? The answer lies in what social psychologists call "herd behavior." Mauritius has perfected the art of channeling group psychology through ethnic and religious identity. Elections become rituals of communal belonging rather than instruments of policy choice.

Even genuine anger gets absorbed into the system. Social media provides the sensation of resistance without consequences—outrage flares, circulates, and subsides while the underlying structure remains intact. Citizens are conditioned to feel grateful for any government spending, even when it represents a tiny fraction of wealth they helped generate.

This psychological capture is reinforced through patronage networks that distribute just enough benefits to maintain loyalty while preserving elite control. A scholarship here, a housing unit there, a government job for a family member—each grain of rice becomes a chain of obligation.

Rights on paper

The Mauritian Constitution promises fundamental rights modeled on Westminster democracy. Chapter II guarantees liberty, equality, and dignity. In practice, these protections are systematically undermined.

Since independence, not a single police officer has been convicted for custodial deaths, despite regular allegations of brutality. Preventive detention laws allow arbitrary arrest. Prison conditions violate international standards. Media outlets face subtle but persistent intimidation. Public appointments follow ethnic quotas that entrench communal divisions.

Mauritius has ratified major international human rights treaties, yet violations persist with impunity. The gap between legal promises and lived reality reflects a deeper problem: institutions designed to constrain power have been captured by those they were meant to regulate.

From sugar to subsidies

The historical parallel is instructive. For centuries, sugar plantations generated enormous wealth that flowed to colonial masters while enslaved and indentured workers labored in the fields. Independence in 1968 promised to break this pattern. Instead, it was refined.

Today's "rice"—GDP growth, tax revenue, aid flows—follows the same path from public production to private accumulation. Infrastructure projects inflate costs through insider dealing. Subsidies meant for struggling farmers end up benefiting large landowners. Public enterprises overpay for goods and services from politically connected suppliers.

Citizens pay twice: first through taxes and inflated prices, then through reduced public services. It is, as Shakespeare wrote, "a pound of flesh" extracted without visible blood—a slow dismantling of public wealth that leaves citizens grateful for their own dispossession.

The masquerade continues

Recent developments illustrate this dynamic. When global food prices spiked in 2022, the government announced rice subsidies with great fanfare. The subsidy covered basic grades while premium varieties—consumed by wealthier households—remained unsubsidized. The policy provided political theater while preserving economic hierarchy.

Similarly, much-touted digital transformation initiatives channel public funds toward firms with close political ties. Citizens celebrate new fiber-optic networks while data shows little improvement in actual internet speeds or affordability.

Such policies exemplify the rice metaphor: genuine public needs get addressed through mechanisms that ensure elite capture, leaving citizens grateful for inadequate solutions to problems that could be solved more effectively with better governance.

Breaking the cycle

Change requires recognizing that Mauritius faces not a resource problem but a distribution problem. The island generates sufficient wealth to provide decent living standards for all citizens. The challenge is political: breaking elite capture of institutions designed to serve the public interest.

This means moving beyond the psychology of gratitude toward demands for accountability. It means treating constitutional rights as enforceable obligations rather than aspirational goals. Most fundamentally, it means recognizing that in a genuine democracy, citizens should not need to be grateful for their own rice.

Until Mauritians move beyond herd behavior and demand control over their own warehouses, the masquerade will continue. The rice will remain abundant, the people will stay hungry, and politicians will keep demanding gratitude for crumbs.

Notes & methodology

This article synthesizes official government documents, IMF Article IV consultations, the Truth and Justice Commission report (2011), and recent statistical releases where cited. Qualitative assessments are derived from comparative political economy literature on elite capture and institutional performance.