Mauritius’ Hidden Lifeline: The Diaspora Remittance Economy

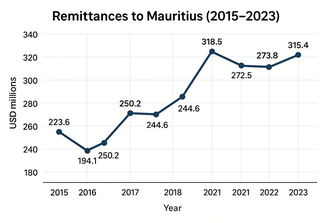

Mauritius receives between USD 250–320 million annually from its diaspora, equivalent to roughly 2% of GDP. For households, these flows mean food on the table, rent covered, tuition fees paid. For the nation, they are a silent stabiliser of reserves and foreign exchange. This quiet reality rarely makes headlines. Yet without it, the island would be far weaker than it admits.

The paradox of departure and return

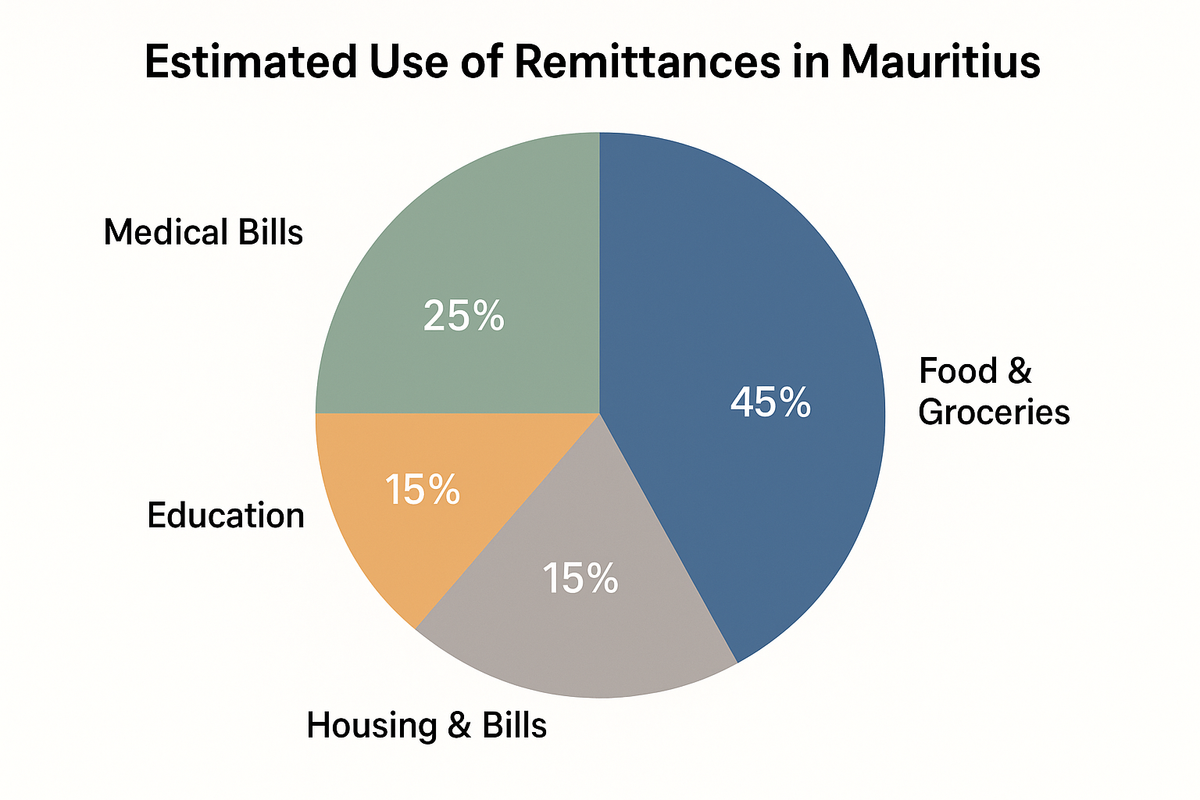

The paradox is cruel. Mauritians leave because they cannot make ends meet at home, yet their departure becomes the very thing that sustains those who remain. Nurses who cannot find stable contracts in Mauritius are welcomed by hospitals in London; engineers who earn too little at home drive taxis in Paris; accountants who dream of careers abroad work night shifts in Canadian warehouses. Their sacrifice translates into remittances — small but steady streams of foreign exchange that rescue families from collapse.

This system does not build local resilience; it externalises it. The nation exports its people, imports their earnings, and sustains consumption rather than development. The cycle repeats with each generation.

Where the money goes

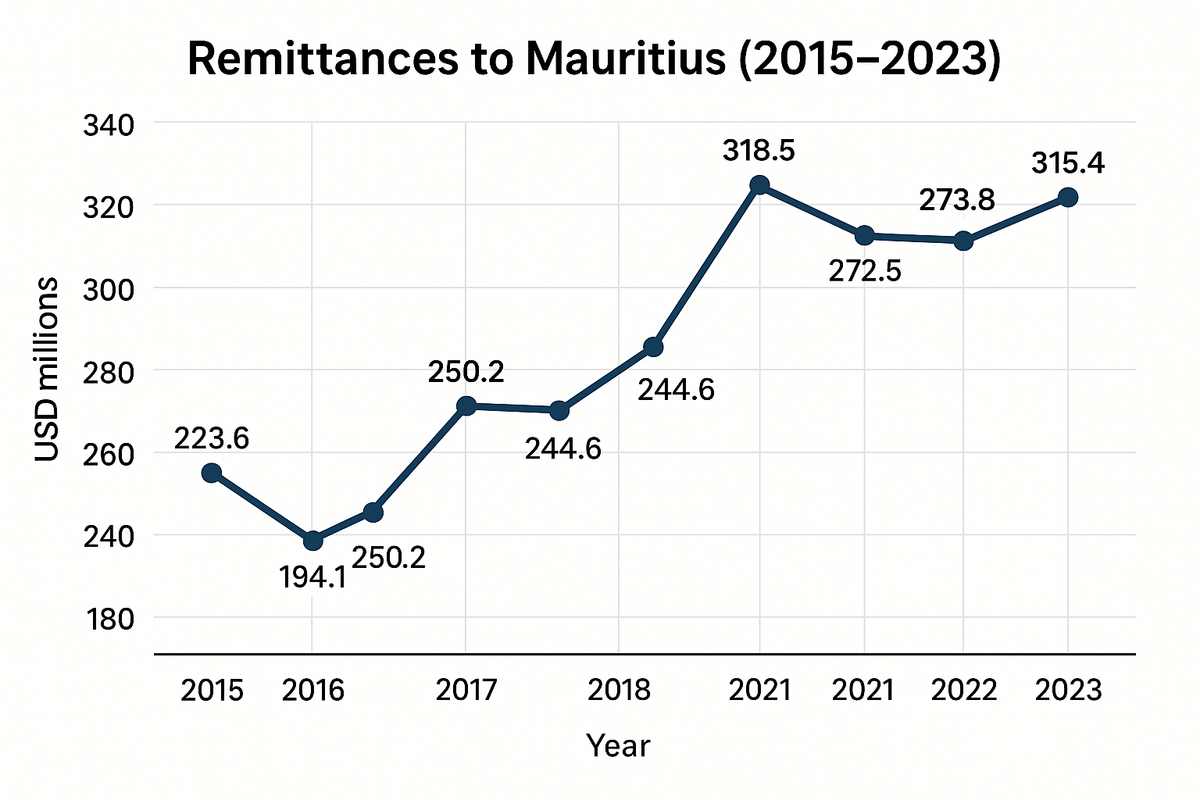

Over 70% of remittances in Mauritius go straight into household consumption: groceries, school fees, hospital bills, rent, and utility payments. Another 15% is absorbed into debt repayment, mostly bank loans and microfinance obligations. Only a sliver — less than 10% — is ever saved or invested productively. Unlike foreign investment, remittances do not create factories or industries; they create breathing space.

Economists sometimes call this the “consumption trap.” Money arrives from abroad but leaks immediately back out through imports: wheat from Ukraine, rice from India, cooking oil from Malaysia, petrol from the Gulf. In this way, the remittance dollar circulates not in Mauritius, but across global supply chains.

A fragile dependence

Government statistics count remittances as part of national accounts, flattering GDP growth and masking weaknesses in the external sector. But this dependence is fragile. If Europe tightens immigration, if the UK reduces foreign worker quotas, if Australia enforces stricter student visa rules, remittance flows could fall. A recession in host countries would ripple instantly across Mauritian households. Few small island states are as vulnerable to external labour-market shocks as Mauritius.

The IMF’s 2024 External Sector Assessment flagged precisely this point: Mauritius’ external balance is sustained less by exports or FDI than by remittances and offshore financial inflows — both highly sensitive to global volatility.

The rupee trap

Remittances enter in hard currencies but are converted into rupees, temporarily shoring up foreign reserves. Yet this masks the chronic weakness of the currency. A USD 100 transfer in 2015 bought nearly Rs 3,400 worth of goods; in 2025, after years of depreciation, it buys less than Rs 4,500 — while the cost of imported food and fuel has more than doubled. Families feel the pinch: the treadmill runs faster, but the belt carries them backwards.

Who really benefits?

At first glance, it is Mauritian families who benefit. But a deeper look shows the ultimate winners are foreign suppliers: the Indian rice miller, the French pharmaceutical exporter, the Emirati fuel trader. Each remitted dollar strengthens Mauritius’ consumption capacity, but equally reinforces the island’s dependence on imports. The diaspora pays, the Mauritian family survives, but the global supplier profits.

The invisible welfare state

Mauritius has, in effect, outsourced its welfare state to its diaspora. Western Union outlets in Quatre Bornes and Flacq are as vital as clinics or schools. Families organise their budgets around “the day the money arrives.” The transfer determines whether a child’s tuition is paid, whether an operation goes ahead, whether a family eats meat this week. In a country where social security nets are frayed, it is emigrants — not the state — who keep the system afloat.

The cost of silence

Politicians remain silent because remittances flatter the numbers. They are celebrated as if they were foreign investment, when in reality they are survival transfers. No factory has been built from this money, no port modernised, no railway laid. The silence is dangerous: it disguises fragility as resilience and dependency as sovereignty.

A question for the future

The long-term risk is generational. Today’s first-generation migrants, who feel a deep obligation to remit, will retire. Their children, born in Paris, Melbourne, or Toronto, may not feel the same ties. When remittances decline — as history suggests they will — Mauritius risks a sudden shock to household incomes, consumption, and reserves. Unless the island finds a growth model beyond exporting its people, the crisis will be quiet, invisible, and inevitable.

Notes & methodology

Data from World Bank and IMF remittance reports, 2015–2024. Bank of Mauritius statistics also referenced, though inconsistencies exist. Household expenditure breakdown based on survey data and academic studies of remittance use in small island economies. Rupee depreciation drawn from IMF exchange rate archives and local inflation indices. All values USD unless otherwise stated.