As I See It

Vayu Putra

Chapter 17

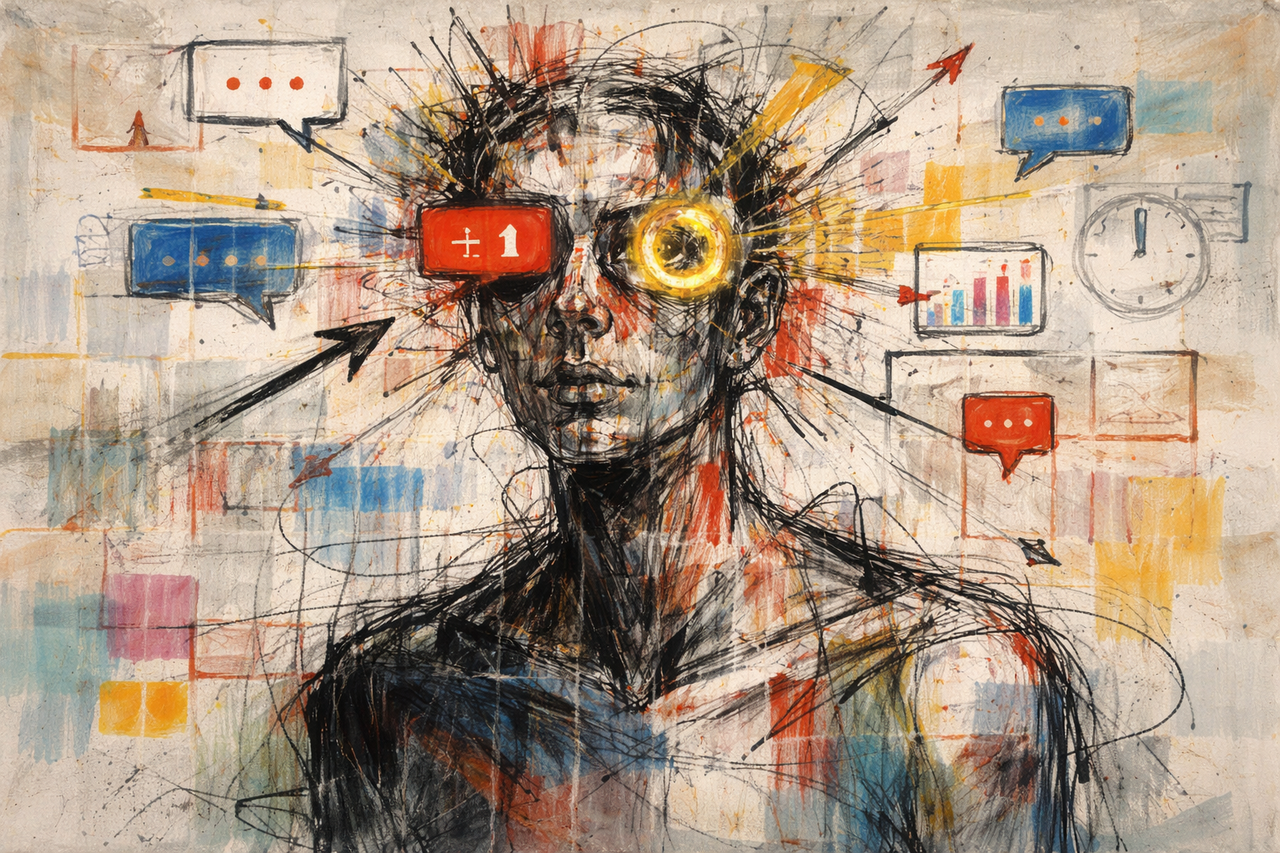

The Economy of Attention

You sit down to read a book, phone placed face-down beside you.

Within three minutes, you check the phone. Nothing important, just reflex. You return to the book but your mind drifts. The paragraph you just read leaves no trace. You read it again, but notifications arrive: email, message, news alert. Each interruption fragments concentration further. After twenty minutes attempting to read, you have absorbed perhaps two pages and checked your phone seven times.

This is not personal failure but design success. Your attention has been systematically trained for fragmentation. Every platform, every device, every interface competes to capture whatever focus remains. The book represents sustained attention requiring patience and depth. The phone offers immediate stimulation requiring neither. The competition is unequal.

Attention has become the scarcest and most valuable resource in the modern economy. Whilst traditional resources like land, labour, and capital remain important, the constraint determining success across industries is increasingly the capacity to capture and retain human attention. Technology companies, advertisers, politicians, media organisations, and social movements all compete in this zero-sum marketplace where your consciousness is the prize.

This chapter examines how attention became commodity, why fragmentation serves economic interests, what neuroscience reveals about sustained focus and its destruction, how silence and depth are systematically eliminated, and why reclaiming attention represents crucial form of resistance in an economy designed to extract it.

Attention as economic resource

Economist Herbert Simon recognised in 1971 that "a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention." As information became abundant, attention became scarce. This scarcity creates economic value. Whoever controls attention controls access to consciousness, making attention the fundamental resource of information age.

The attention economy functions differently from traditional economics. Goods can be produced and consumed by multiple people. Attention cannot. You possess limited conscious awareness that must be allocated across competing demands. When you attend to one thing, you cannot simultaneously attend to another. This makes attention genuinely scarce regardless of technological abundance.

Technology historian Tim Wu's "The Attention Merchants" (2016) documents how commercial exploitation of attention evolved from 19th-century newspapers through radio, television, and internet. Each medium refined techniques for capturing attention and converting it to profit. The basic model remains constant: provide content attracting attention, then sell that attention to advertisers.

What changed with digital technology is scale and sophistication. Television advertisers bought audiences aggregated by programme. Digital platforms sell individualised attention targeted through behavioural data. This allows unprecedented precision in matching advertisements to predicted receptivity, making attention more valuable whilst making extraction more invasive.

The statistics reveal attention's economic magnitude. Global digital advertising exceeded $600 billion in 2024, with Google and Facebook capturing over 60% of online advertising revenue. These companies produce no content; they aggregate and sell attention. Their market capitalisations reflect attention's value: controlling how billions allocate consciousness generates enormous wealth.

Research shows average person encounters 6,000 to 10,000 advertisements daily when accounting for logos, brand placements, and sponsored content. This represents industrialised assault on consciousness. Each advertisement competes for attention that could be directed elsewhere. The cumulative effect is perpetual low-level distraction.

Philosopher Matthew Crawford's "The World Beyond Your Head" (2015) argues that attention has become "our last remaining privately held resource." In attention economy, your consciousness is disputed territory that commercial interests constantly attempt to colonise. Maintaining ownership of your own attention requires active defence against systems engineered to capture it.

The neuroscience of attention and distraction

Attention is not single faculty but multiple brain systems working in concert. Understanding these systems reveals why digital environments prove so disruptive to sustained focus and why reclaiming attention requires more than willpower.

Neuroscience distinguishes bottom-up attention (stimulus-driven, automatic) from top-down attention (goal-directed, effortful). Bottom-up attention responds to sudden movements, loud sounds, bright colours, novelty. It evolved for survival, automatically orienting to potential threats or opportunities. Top-down attention involves deliberately focusing on chosen tasks whilst filtering distractions.

Digital devices exploit bottom-up attention through design choices triggering automatic orienting responses. Notification badges in red activate threat-detection systems. Vibrations create startle responses. Variable reward timing (you never know when interesting content appears) maintains vigilance. These features hijack evolutionary mechanisms, making distraction neurologically compelling.

Psychologist William James wrote in 1890 that attention is "the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought." This capacity for selective focus enables coherent experience. When attention fragments, experience fragments with it.

Research by cognitive neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley shows that multitasking impairs performance on all tasks attempted simultaneously. Brain imaging reveals that switching between tasks activates prefrontal regions governing executive control. Each switch depletes cognitive resources. Frequent switching creates what Gazzaley calls "continuous partial attention" where nothing receives full processing.

Psychologist Gloria Mark's research documented that it takes average 23 minutes to fully return to task after interruption. Given that knowledge workers experience interruption every three minutes on average, achieving sustained focus becomes nearly impossible. Most people operate in perpetual state of attempted task resumption, never achieving deep concentration.

The anterior cingulate cortex, involved in attention control, shows measurable changes with meditation practice. Studies of long-term meditators reveal increased grey matter density in attention-related brain regions and enhanced capacity for sustained focus. This demonstrates that attention is trainable, but like physical fitness, requires regular practice against cultural currents favouring distraction.

Dopamine systems complicate attention further. Novel stimuli trigger dopamine release creating pleasurable anticipation. Digital platforms exploit this by engineering unpredictability: you never know what the next scroll will reveal. This variable reward schedule, identical to gambling mechanics, makes distraction neurologically rewarding.

The destruction of deep attention

Literary scholar N. Katherine Hayles distinguishes "deep attention" from "hyper attention." Deep attention involves sustained focus on single object over extended periods, necessary for complex thinking, reading, and creative work. Hyper attention involves rapid switching between multiple stimuli, optimised for quickly scanning information-rich environments.

Modern culture systematically selects for hyper attention whilst eliminating contexts supporting deep attention. Educational systems increasingly emphasise rapid information processing over sustained contemplation. Workplaces reward responsiveness over reflection. Media consumption shifts from long-form content to fragments optimised for viral spread.

Research shows declining ability for sustained attention across populations. Studies tracking reading patterns find that deep reading, where readers lose themselves in text for extended periods, has decreased dramatically. Students report difficulty reading textbook chapters without frequent breaks for checking devices. This represents measurable cognitive change.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's research on "flow" states describes optimal experience occurring during deep attention. Flow involves complete absorption in challenging activities matching skill level, producing intense focus and intrinsic reward. Research shows flow states generate greatest subjective wellbeing and productivity. Yet digital environments systematically interrupt flow through constant notifications.

Computer scientist Cal Newport's "Deep Work" (2016) argues that capacity for sustained concentration on cognitively demanding tasks has become simultaneously rare and valuable. As more people lose deep attention capacity, those maintaining it gain competitive advantage. Yet the economic incentives push towards eliminating rather than cultivating this capacity.

Neuroscience reveals that different types of thinking require different attention patterns. Analytical problem-solving benefits from focused attention. Creative insight often emerges during diffuse attention where mind wanders productively. Social understanding requires sustained attention to others' emotions and contexts. Digital fragmentation impairs all these modes by preventing sustained engagement.

Research on attention restoration theory by environmental psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan shows that natural environments restore depleted attention. Looking at nature, even through windows or photographs, reduces mental fatigue and improves concentration. Urban environments, particularly those filled with advertisements and digital screens, intensify attention demands without providing restoration.

Fragmentation as design principle

Digital platforms profit from fragmented attention. Sustained focus on single content means fewer advertisements viewed, less data generated, reduced engagement metrics. This creates economic incentive to fragment attention as thoroughly as possible whilst keeping users on platform.

Interface design reflects this logic. Infinite scroll eliminates natural stopping points. Auto-play queues next content automatically. Related content suggestions appear constantly. Comment sections create controversy demanding response. These features do not serve user interests in comprehension or satisfaction but platform interests in continued engagement.

Research on digital reading shows that hypertext, whilst enabling rapid navigation, impairs comprehension compared to linear reading. Studies tracking eye movements reveal that online reading involves more scanning and skimming, less deep processing. The medium's structure encourages fragmented rather than sustained attention.

News consumption illustrates fragmentation's effects. Traditional newspapers presented hierarchical information allowing readers to judge importance and allocate attention accordingly. Digital news feeds present flattened streams where celebrity gossip, international conflict, and personal updates appear indistinguishable, each competing equally for attention through emotional triggers rather than significance.

Journalist Johann Hari's "Stolen Focus" (2022) documents systematic theft of attention through technological design, dietary changes affecting cognition, environmental pollutants impairing concentration, increased stress and sleep deprivation, and elimination of childhood free play. The problem is not individual weakness but structural assault on attention from multiple directions.

Social psychologist Sherry Turkle's research on conversation shows that mere presence of phones on table reduces conversation quality and emotional intimacy. Participants report less connection and empathy when phones are visible even if not used. The possibility of interruption fragments attention to present interaction.

Fragmentation extends beyond individual experience to collective attention. Research on news cycles shows dramatic acceleration. Stories that would dominate attention for weeks now cycle through public consciousness in days or hours. This makes sustained engagement with complex issues nearly impossible as attention constantly shifts to latest crisis or outrage.

The elimination of silence and boredom

Modern culture treats silence and boredom as problems requiring technological solution. Yet neuroscience reveals that both are psychologically necessary. Eliminating them impairs cognition whilst serving economic interests in continuous consumption.

Research on default mode network, brain regions active during rest and mind-wandering, shows these states are not idle but cognitively productive. Memory consolidation, self-reflection, moral reasoning, imagination, and problem-solving all occur during apparent downtime. Constant stimulation prevents these essential processes.

Psychologist Timothy Wilson's research demonstrated that people would rather receive mild electric shocks than sit quietly with thoughts for fifteen minutes. This reveals profound discomfort with unstructured mental space. Rather than learning to tolerate and use this space productively, culture provides endless stimulation enabling permanent avoidance.

Every empty moment becomes opportunity for content consumption. Waiting in queue, riding elevators, walking between locations all trigger phone-checking reflexes. Research shows average person checks phone 96 times daily, roughly every ten minutes during waking hours. This eliminates transitional spaces where mind could wander productively.

Boredom serves important functions. Research shows that boredom motivates exploration and creativity. When understimulated, people seek novel experiences and generate creative solutions. Providing constant entertainment eliminates boredom whilst eliminating its benefits, creating passive consumers rather than active agents.

Silence enables different quality of attention. Research on meditation and contemplative practices shows that sustained silence produces measurable neurological changes: increased grey matter in attention and emotion regulation regions, enhanced capacity for present-moment awareness, reduced rumination and anxiety. Yet modern life systematically eliminates contexts where silence can occur.

Philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues in "The Burnout Society" (2015) that achievement-oriented culture creates individuals who exploit themselves whilst experiencing this self-exploitation as freedom. Constant productivity and stimulation appear as personal choices rather than structural demands. The inability to tolerate silence reflects internalisation of economic logic requiring perpetual activity.

Religious and philosophical traditions recognised silence's necessity. Contemplative monasticism, meditation practices, philosophical retreats, and artistic creation all involved extended periods of quiet. These were not escapes from reality but methods for perceiving reality more clearly. Contemporary culture treats such practices as luxuries rather than necessities.

Attention and empathy

Empathy requires sustained attention to another person's emotional state, context, and perspective. Research shows empathy depends on neural systems that activate when giving focused attention to others. Fragmented attention impairs empathy by preventing sustained engagement necessary for understanding.

Neuroscientist Jean Decety's research on empathy shows it involves both automatic emotional resonance and deliberate perspective-taking. The automatic component activates quickly when witnessing others' distress. The deliberate component requires sustained attention to understand others' situations fully. Digital fragmentation may preserve automatic responses whilst impairing deliberate understanding.

Research by psychologist Sara Konrath documented declining empathy amongst American college students from 1979 to 2009, with sharpest declines after 2000 coinciding with internet and smartphone adoption. Students showed reduced perspective-taking and empathic concern. Whilst correlation does not prove causation, the timing suggests digital culture may contribute to empathy erosion.

Social media creates paradox: more connection alongside less empathy. Platforms enable contact with more people but incentivise shallow engagement. Research shows that passive social media consumption (scrolling without interacting) reduces wellbeing and empathy whilst active engagement (direct conversation) maintains both. Yet platform design encourages passive consumption.

Online interaction eliminates many cues supporting empathy: facial expressions, tone of voice, body language, shared physical context. Research shows this makes misunderstanding more likely and empathic accuracy more difficult. Text-based communication selects for quick reactions over thoughtful responses, privileging outrage over understanding.

Psychologist Sherry Turkle's research in "Reclaiming Conversation" (2015) shows that face-to-face conversation builds empathy whilst screen-mediated communication depletes it. Conversations require sustained mutual attention, turn-taking, tolerance for silence, and vulnerability. These practices develop empathic capacity. Digital communication often bypasses them.

Research on reading literary fiction shows it improves empathy and theory of mind (understanding others' mental states). Deep reading requires entering characters' perspectives and maintaining attention through complex narratives. As deep reading declines, this empathy training diminishes. The shift from novels to fragments may have moral consequences.

Political consequences of attention extraction

Democracy requires informed citizens capable of sustained attention to complex issues. Attention economy systematically undermines these requirements by fragmenting focus, prioritising emotional intensity over analysis, and accelerating news cycles beyond comprehension capacity.

Political discourse adapted to attention scarcity through simplification and sensationalism. Research shows that nuanced policy positions generate less engagement than dramatic claims and personal attacks. Platforms' algorithmic ranking rewards content triggering strong emotions, making measured analysis less visible than outrage.

Media scholar danah boyd's research on "context collapse" in social media shows how platforms flatten distinct audiences into single feed. Politicians can no longer tailor messages to specific constituencies without risking exposure to all audiences simultaneously. This incentivises vague platitudes or tribal signalling over substantive positions requiring explanation.

Attention economy favours spectacle over governance. Research tracking media coverage shows that Trump's presidency generated unprecedented attention through constant provocation. Whether coverage was positive or negative mattered less than volume. This demonstrates that attention itself, regardless of valence, confers political advantage in attention economy.

Political scientist Matthew Hindman's research on digital politics shows that whilst internet theoretically democratises political participation, attention remains highly concentrated. Small number of websites, accounts, and influencers capture disproportionate attention. The promise of diverse voices is undermined by winner-take-all dynamics in attention markets.

Issue attention cycles accelerate beyond policy capacity to respond. Research by political scientist Frank Baumgartner shows that media attention to issues spikes rapidly then declines before policy solutions can be implemented. This creates perpetual crisis atmosphere where problems appear urgent then forgotten before addressing them, replaced by next attention-capturing event.

Philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues that fragmented attention destroys capacity for political judgement. Democracy requires citizens capable of sustained reflection on complex issues, tolerance for ambiguity, and willingness to revise opinions based on evidence. Attention economy produces subjects optimised for consumption and reaction rather than deliberation.

Reclaiming attention as resistance

If attention is primary resource of contemporary capitalism, protecting attention represents crucial form of resistance. This does not require rejecting technology entirely but developing critical consciousness about attention's value and deliberate practices for maintaining control.

Research on attention training through meditation shows measurable improvements in sustained focus, working memory, and emotional regulation. Studies comparing experienced meditators with controls find enhanced ability to maintain attention on chosen objects whilst resisting distraction. This demonstrates that attention is trainable capacity, not fixed trait.

Simple practices prove effective. Research shows that turning off notifications dramatically reduces interruptions and improves concentration. Studies where participants disabled notifications for one week report decreased stress and increased productivity without missing important communications. The perception that constant availability is necessary proves largely illusory.

Creating technology-free times and spaces restores attention capacity. Research on digital detox interventions shows that even brief periods without devices improve mood, sleep quality, and relationship satisfaction. Designating meal times, mornings, or bedrooms as device-free creates sanctuaries where sustained attention becomes possible.

Reading long-form content trains sustained attention depleted by constant scanning. Research comparing brain activity during book reading versus web browsing shows distinct patterns. Deep reading activates extensive networks supporting comprehension, empathy, and memory. Regular practice can restore capacities eroded through years of fragmented consumption.

Philosopher Matthew Crawford advocates "attentional commons" where public spaces remain free from commercial demands on consciousness. This could include advertising-free zones, quiet carriages on trains, and technology-free areas in schools and workplaces. Such spaces assert that not all attention should be available for commercial extraction.

Research on flow states by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi shows that people report greatest happiness during deep absorption in challenging activities. Yet modern culture systematically interrupts flow through constant connectivity. Protecting extended periods for focused work or creative pursuits provides both productivity and wellbeing benefits.

Structural changes would support individual efforts. Regulatory frameworks could limit advertising in public spaces, require platforms to disclose attention manipulation techniques, and establish rights to uninterrupted time. France's "right to disconnect" law, allowing workers to ignore work communications outside office hours, demonstrates feasibility of protecting attention through policy.

The awareness economy as alternative

Attention economy measures success through metrics: views, clicks, time on site. These quantify attention as resource extracted and monetised. An alternative framework, the awareness economy, would measure success through quality of consciousness: comprehension, reflection, wellbeing, connection.

This represents fundamental values shift from extraction to cultivation. Rather than mining attention as rapidly as possible, awareness economy would nurture sustained focus enabling genuine understanding. Rather than fragmenting consciousness for profit, it would protect conditions allowing coherent experience.

Educational systems oriented towards awareness would reward depth over speed, contemplation over coverage, understanding over information accumulation. Research on educational quality consistently shows that sustained engagement with fewer topics produces better learning than rapid coverage of many. Yet standardised testing and curriculum pressures push towards fragmentation.

Media designed for awareness would prioritise comprehension over clicks. This might mean longer articles with context rather than breaking news fragments, fewer but more substantial updates rather than constant streams, and design encouraging thoughtful reading rather than rapid scrolling. Some publications are experimenting with such models.

Workplaces valuing awareness would protect time for deep work, minimise meetings and interruptions, and judge productivity by meaningful output rather than visible busyness. Research by organisational psychologists shows that knowledge workers need several hours of uninterrupted time for complex thinking, yet most experience constant fragmentation.

Technology serving awareness would include tools helping users track and limit device usage, interfaces minimising distraction rather than maximising engagement, and platforms connecting people meaningfully rather than maximising time on site. Examples include distraction-free writing applications, meditation apps, and reader modes stripping websites to essential text.

The shift from attention to awareness economy would require recognising that human flourishing depends on sustained focus, that consciousness has intrinsic value beyond economic extraction, and that protecting attention is protecting the conditions for meaningful life. This is cultural transformation as much as economic restructuring.

Connection to previous chapters

Attention economy represents synthesis of mechanisms explored throughout this book, applying them through technological systems designed to capture and monetise consciousness itself.

Consciousness (Chapter 2): Attention economy directly targets consciousness, attempting to capture awareness for commercial purposes. The burden of consciousness increases as individuals must defend their own mental space against constant invasion.

Masks (Chapter 3): Fragmented attention impairs capacity to distinguish authentic self from performed roles. Constant external orientation prevents reflection necessary for knowing which aspects of self-presentation are genuine versus strategic.

Crowds (Chapter 4): Digital platforms aggregate attention into virtual crowds where individual focus dissolves into collective reactions. Trending topics function as crowd phenomena accelerated to internet speed.

Indoctrination (Chapter 5): Fragmented attention makes indoctrination easier by preventing sustained critical examination. Platforms can shape beliefs through accumulated exposure to fragments rather than requiring engagement with coherent arguments.

Early belief systems (Chapter 6): Attention economy creates new belief systems where metrics become sacred, engagement becomes moral good, and visibility becomes measure of worth. These function religiously despite secular framing.

Capitalism (Chapter 7): Attention economy extends capitalism into consciousness itself. Rather than selling labour, people unknowingly sell attention. Rather than extracting resources from nature, system extracts awareness from minds.

Hypernormalisation (Chapter 8): Everyone knows attention is being manipulated yet continues participating because alternatives seem impossible. The gap between awareness of exploitation and capacity to resist creates hypernormalised relationship with technology.

Control without violence (Chapter 9): Attention extraction represents ultimate control without violence. Rather than forcing compliance, systems engineer desire and exploit neurological vulnerabilities, making exploitation feel like free choice.

Identity as weapon (Chapter 10): Fragmented attention impairs empathy necessary for recognising shared humanity across identity boundaries. Platforms profit from identity-based conflict by capturing attention through outrage and tribal signalling.

Mental health (Chapter 11): Systematic attention fragmentation contributes directly to mental health crisis through sleep disruption, anxiety from constant connectivity, depression from social comparison, and cognitive exhaustion from perpetual stimulation.

Education (Chapter 12): Attention economy undermines education by training fragmented scanning rather than sustained focus. Students conditioned for rapid information consumption struggle with deep learning requiring patience and concentration.

Radicalisation (Chapter 13): Fragmented attention makes people susceptible to radicalisation by preventing sustained examination of ideological claims. Platforms can guide users towards extremism through accumulated exposure without requiring deliberate commitment.

Individuality (Chapter 14): Independent thought requires sustained attention resisting social pressure and algorithmic curation. Fragmentation makes individuality harder by eliminating mental space where genuine reflection occurs.

Secular sacred (Chapter 15): Attention economy commodifies consciousness that secular sacred framework identifies as fundamentally worthy of protection. Treating awareness as resource for extraction violates basic ethical commitment to protect conscious experience.

Algorithmic mind (Chapter 16): Algorithms optimise attention extraction through personalisation, recommendation systems, and interface design. Previous chapter examined algorithmic governance; this chapter examines what algorithms govern: the most fundamental resource of conscious experience.

Conclusion: defending consciousness

This chapter has documented how attention became the fundamental economic resource of information age, how fragmentation serves commercial interests whilst destroying cognitive capacities, what neuroscience reveals about attention's mechanisms and vulnerabilities, and why reclaiming attention represents crucial resistance.

The research presented demonstrates that attention is genuinely scarce resource. Unlike information, which can be infinitely copied, attention is limited to what consciousness can process. This scarcity creates economic value exploited through increasingly sophisticated extraction techniques.

Neuroscience reveals mechanisms underlying attention and distraction. Bottom-up attention responds automatically to stimuli engineered into digital environments. Top-down attention requires effortful focus constantly interrupted. Multitasking depletes cognitive resources whilst creating illusion of productivity. The brain adapts to fragmentation by weakening capacities for sustained focus.

Deep attention, necessary for complex thinking, creative work, and empathic understanding, systematically declines as culture selects for hyper attention optimised for rapid scanning. Research documents measurable changes: reduced reading comprehension, impaired memory formation, decreased empathy, and accelerated news cycles beyond comprehension capacity.

Fragmentation functions as design principle serving economic interests. Platforms profit from constant engagement requiring perpetual distraction. Infinite scroll, auto-play, notifications, and algorithmic recommendations all engineer attention fragmentation whilst appearing to serve user interests in personalisation and convenience.

Silence and boredom, psychologically necessary for memory consolidation, creativity, and self-reflection, are systematically eliminated. Research shows that constant stimulation impairs default mode network functions essential for coherent selfhood. Yet culture treats unstructured mental time as waste rather than necessity.

Empathy requires sustained attention to others' perspectives and contexts. Research documents declining empathy correlating with digital media adoption. Fragmented attention preserves automatic emotional responses whilst impairing deliberate perspective-taking necessary for genuine understanding across difference.

Political consequences include shift from deliberation to reaction, from nuance to spectacle, from policy to performance. Democracy requires sustained attention to complex issues, but attention economy rewards emotional intensity over analysis. This creates governance crisis where problems cycle through public awareness without resolution.

Yet resistance remains possible through awareness and practice. Research on meditation, digital minimalism, and attention training shows that sustained focus is developable skill. Simple interventions like disabling notifications, creating technology-free times, and practising deep reading demonstrate effectiveness.

The awareness economy framework proposes alternative values: measuring success through comprehension rather than clicks, protecting conditions for sustained focus rather than engineering fragmentation, treating consciousness as intrinsically valuable rather than resource for extraction.

The opening scenario of attempting to read whilst constantly checking phone illustrates attention economy operating practically. The book represents deep attention requiring patience. The phone offers fragments demanding nothing. The competition is rigged. Without deliberate resistance, fragmentation wins by default.

What makes attention economy distinct is that it directly targets consciousness itself. Previous economic systems exploited labour, land, and capital. Attention economy extracts the fundamental resource enabling experience: awareness. This makes it simultaneously more invasive and more invisible than earlier forms of exploitation.

The chapter argues that protecting attention is protecting the conditions for meaningful human life. Consciousness fragmented into commercial opportunities cannot sustain complex thought, empathic connection, creative expression, or democratic deliberation. These require sustained focus that attention economy systematically destroys.

Reclaiming attention requires recognising its value and defending it deliberately. This is not rejecting technology but refusing to let it operate unconsciously. Every moment of sustained focus represents victory against systems optimised for fragmentation. Every period of silence restores capacities depleted through constant stimulation.

The secular sacred framework from Chapter 15 provides ethical foundation: consciousness itself is sacred because once destroyed it cannot be restored. Attention is gateway to consciousness. Protecting attention is protecting what makes us human: the capacity for awareness, reflection, understanding, and choice.

Whether individuals and societies can resist attention extraction whilst embedded in systems engineered to capture it remains uncertain. The forces promoting fragmentation are powerful, sophisticated, and profitable. Yet awareness of these dynamics creates possibility for resistance through conscious choice about where attention goes.

In world where attention determines reality, controlling attention means controlling experience itself. The war for consciousness is not metaphor but description of contemporary condition. The question is whether enough people will recognise this and choose to defend their awareness against systems designed to extract it, or whether attention will continue fragmenting until sustained thought becomes impossible and consciousness becomes pure reaction to engineered stimuli.

End of Chapter 17