As I See It

Vayu Putra

Chapter 21

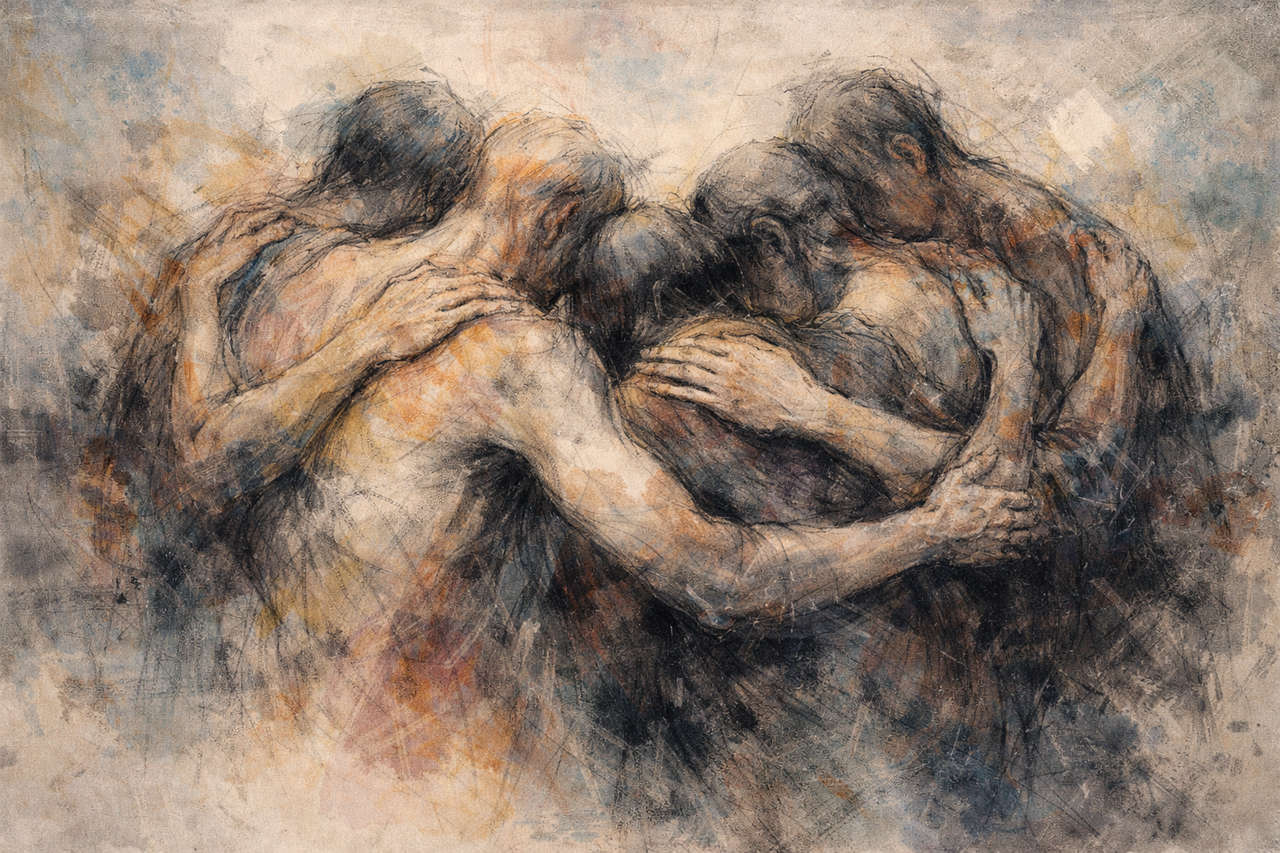

Collective Healing

You are sitting in a circle with neighbours discussing how to address rising costs collectively.

The meeting began awkwardly. People barely know each other despite living on the same street for years. Someone suggests a bulk-buying cooperative; another proposes tool-sharing. A third person mentions elderly residents who need help with shopping. The conversation meanders, occasionally stumbles into disagreement about politics or whose responsibility various problems are.

Yet something shifts as people continue talking. The defensive postures soften slightly. Someone admits they have been struggling financially, thought everyone else was managing fine. Others nod in recognition. The pretence of individual competence drops enough for actual problems to become visible. Not solved, but acknowledged.

By the meeting's end, modest commitments emerge: sharing garden tools, coordinating bulk orders, creating informal support network. Nothing revolutionary. But in room exists something absent before: recognition that isolation is choice, not inevitability. That mutual aid represents practical option, not utopian fantasy.

Walking home, you notice the street differently. These buildings contain not abstract neighbours but specific people facing concrete challenges, some now known. The individualist narrative maintaining separation weakens slightly. Community, usually invoked abstractly, feels momentarily tangible.

This chapter examines what collective healing means after understanding mechanisms maintaining division, why societies heal differently than individuals, what research reveals about communities recovering from trauma and building alternatives, how healing requires mourning what was lost, and why collective transformation happens through accumulated small practices rather than revolutionary ruptures.

The nature of collective trauma

Collective trauma differs from individual trauma whilst sharing fundamental characteristics. When entire communities experience overwhelming events, war, genocide, disasters, economic collapse, or systematic oppression, trauma affects social fabric itself. Trust erodes, narratives fracture, shared reality becomes contested.

Research on collective trauma shows that societies experiencing mass violence or sustained crisis develop characteristic patterns: hypervigilance toward perceived threats, difficulty trusting institutions or outsiders, conflicting narratives about what occurred, and transmission of trauma responses across generations even among those not directly affected.

Studies of post-conflict societies reveal that trauma does not end when violence stops. Rwanda decades after genocide, Cambodia after Khmer Rouge, communities throughout Balkans after Yugoslav wars all show lasting effects: elevated mental health problems, difficulty establishing stable governance, cycles of mistrust and retaliation.

Economic trauma proves equally powerful though less visibly violent. Communities experiencing deindustrialisation, austerity, or systemic poverty show patterns resembling PTSD at population level: loss of social cohesion, increased substance abuse, political extremism, shortened life expectancy. The collapse of shared economic security creates collective wound affecting generations.

Environmental trauma emerges as communities face displacement from climate disasters, loss of traditional livelihoods, or toxic contamination. Research shows that environmental destruction affects not just material conditions but cultural identity, particularly for indigenous communities and places where environment intertwines with social meaning.

Political trauma occurs when governments betray trust, democratic institutions fail, or systematic corruption becomes undeniable. Populations lose faith in collective capacity to address problems through legitimate means. This disillusionment creates vacuum easily filled by authoritarianism, conspiracy theories, or cynical disengagement.

What makes collective trauma especially intractable is that it affects the very mechanisms needed for healing. Individual trauma therapy relies on safe relationships and regulated nervous systems. Collective trauma damages social trust and creates populations operating in chronic stress states. The tools for healing become less accessible precisely when most needed.

Truth, acknowledgement, and collective memory

Collective healing requires truth-telling about what occurred. Societies cannot heal wounds they refuse to acknowledge. Yet establishing shared truth proves extraordinarily difficult when events are contested, power asymmetries persist, and different groups experienced same events entirely differently.

Truth and reconciliation commissions represent structured attempts at collective truth-telling. South Africa's post-apartheid commission, whilst imperfect, demonstrated that publicly acknowledging systematic harm serves healing function even without complete justice. Research shows that victims reporting being heard experienced psychological benefits regardless of whether perpetrators faced consequences.

Studies comparing societies with and without formal truth-telling mechanisms show mixed results. Some truth commissions successfully established shared historical narratives reducing denial. Others became politicised, serving victor's justice rather than genuine accountability. The difference appears to lie in genuine commitment to hearing all perspectives versus using truth-telling for political legitimisation.

Collective memory research reveals how societies construct narratives about past events. These narratives serve present political purposes as much as historical accuracy. Comfortable myths erase inconvenient truths. Heroic stories omit systematic violence. National identities require forgetting as much as remembering.

The politics of apology demonstrates complexities of collective acknowledgement. When governments apologise for historical wrongs, slavery, genocide, forced assimilation, does this constitute meaningful repair or performative gesture? Research suggests that apologies prove most meaningful when coupled with material reparations and structural changes rather than symbolic statements alone.

Memorialisation serves important function in collective healing by creating physical spaces acknowledging what occurred. Holocaust memorials, slavery museums, sites commemorating genocides all provide locations where collective mourning can occur. Yet memorials can also become contested when different groups have competing narratives about whose suffering deserves recognition.

The challenge is that truth-telling threatens those who benefited from or participated in harm. Research on resistance to historical reckoning shows predictable patterns: minimising severity, claiming everyone suffered equally, arguing that contemporary people should not be held responsible for past actions, insisting on moving forward without dwelling on negatives.

Restorative justice and accountability

Restorative justice offers alternative to purely punitive approaches by focusing on repairing harm rather than inflicting punishment. The approach brings together those harmed, those who caused harm, and affected community to address consequences and determine how to make things right.

Research on restorative justice programmes shows generally positive outcomes: higher victim satisfaction than conventional justice, reduced recidivism among offenders, community involvement in addressing harm, and emphasis on accountability through facing consequences rather than avoiding through denial or legal manoeuvring.

Studies comparing restorative with retributive justice reveal important differences in outcomes. Whilst punishment aims to inflict suffering proportional to harm caused, restoration aims to repair damage and reintegrate both victims and offenders into community. Research shows that restorative processes often produce more lasting behaviour change than incarceration alone.

Yet restorative justice faces limitations when power imbalances are severe or when harm is systematic rather than interpersonal. Can restorative approaches address corporate exploitation, state violence, or structural inequality? Some argue that restoration assumes relatively equal parties coming together voluntarily, conditions often absent in cases of systematic oppression.

Accountability proves essential yet complex. Who is accountable when harm is systematic? Research on corporate accountability shows how diffused responsibility allows everyone to disclaim personal culpability whilst collective harm continues. Similar dynamics appear in governmental, military, and institutional contexts where chain of command obscures individual responsibility.

Transformative justice extends restorative principles by addressing root causes of harm rather than individual incidents alone. This approach recognises that interpersonal violence often reflects broader structural violence requiring systemic change alongside individual accountability. Research shows this proves especially important for marginalised communities experiencing both interpersonal and structural harm.

The challenge is balancing accountability with possibility of change. Purely punitive approaches often harden rather than transform. Yet forgiveness without accountability enables continued harm. Collective healing requires finding pathways allowing genuine accountability whilst maintaining possibility that people and systems can change.

Mutual aid and commons

Mutual aid describes voluntary reciprocal exchange of resources and services for common benefit. Unlike charity, which creates hierarchical relationship between giver and receiver, mutual aid operates through solidarity: recognising that individual wellbeing depends on collective wellbeing and that everyone has capacity to contribute and receive support.

Historical research shows mutual aid societies predating modern welfare states. Working-class communities created networks providing healthcare, education, burial insurance, and unemployment support through pooled resources and reciprocal obligations. These institutions demonstrated that communities can organise care without relying solely on markets or states.

Contemporary mutual aid networks resurge during crises when formal institutions prove inadequate. Research on disaster response shows that mutual aid often provides more immediate and contextually appropriate support than bureaucratic relief efforts. Neighbours helping neighbours mobilise faster than official channels can coordinate.

Studies of mutual aid reveal important dynamics. Participation strengthens social bonds, creates networks of trust, and builds collective capacity. People involved report increased sense of agency, belonging, and hope. These psychological benefits alongside material support suggest mutual aid addresses isolation as much as practical needs.

The commons describes resources managed collectively rather than through private ownership or state control. Research on commons governance challenges assumptions that shared resources inevitably face tragedy requiring privatisation or centralised management. Studies show communities successfully managing forests, fisheries, water systems, and grazing lands through locally developed rules and monitoring.

Principles enabling successful commons management include: clearly defined boundaries, rules matching local conditions, collective decision-making, monitoring by community members, graduated sanctions for violations, conflict resolution mechanisms, and autonomy from external authorities. These principles emerge from studying diverse commons systems across cultures and contexts.

Digital commons demonstrate that principles apply beyond physical resources. Open-source software, Wikipedia, and collaborative platforms show that knowledge and cultural resources can be collectively created and maintained. Research shows these commons produce public goods whilst fostering participation and shared stewardship.

Healing through culture

Culture provides crucial medium for collective healing. Art, music, literature, ritual, and ceremony create spaces where trauma can be processed collectively, alternative narratives developed, and new meanings constructed from experiences of loss and suffering.

Research on arts-based healing shows measurable benefits. Community theatre addressing local traumas, music programmes for conflict-affected populations, and collaborative art projects create opportunities for expression, connection, and meaning-making unavailable through clinical interventions alone. These cultural practices activate different healing pathways than talk therapy.

Studies of indigenous healing practices demonstrate sophisticated cultural approaches to collective trauma. Ceremonies, storytelling, and communal rituals address spiritual and social dimensions of healing alongside psychological and physical. These holistic approaches recognise that trauma affects entire being and requires integrated response.

Cultural revitalisation proves especially important for communities whose trauma includes cultural destruction. Research on language reclamation, traditional practice revival, and cultural education shows these efforts restore not just specific practices but sense of continuity, identity, and collective purpose damaged by colonisation or forced assimilation.

Music serves particularly powerful role in collective healing. Studies show that communal singing, drumming circles, and collaborative music-making synchronise nervous systems, create embodied connection, and provide emotional release. Music bypasses verbal processing, accessing emotional experiences difficult to articulate in words.

Narrative practices enable communities to reframe experiences. Research on storytelling shows that how events are narrated affects their integration. Trauma narratives can reinforce victimisation or facilitate empowerment depending on framing. Collective storytelling allows communities to construct shared meanings that honour suffering whilst identifying agency and resilience.

Public ritual provides structure for collective mourning and transformation. Memorials, anniversaries, and ceremonies mark transitions from denial to acknowledgement, from acute grief to integrated loss. Research shows that cultures with robust mourning rituals typically show healthier collective processing of loss than those emphasising moving on quickly.

The possibility of transformation

Social transformation describes fundamental shifts in how societies organise, value, and relate. Unlike reform, which modifies existing structures, transformation changes underlying patterns themselves. Research on major social changes shows these typically emerge not from single revolutions but through accumulated shifts in consciousness, practice, and possibility.

Studies of successful social movements reveal common elements: clear analysis of problems, compelling vision of alternatives, strategic action disrupting business as usual, building parallel institutions demonstrating viability, and cultural work shifting values and norms. Movements fail when they excel at critique but offer no alternative or when alternatives remain abstract rather than practically demonstrated.

Historical research shows that major transformations often appear impossible until suddenly inevitable. Slavery's abolition, women's suffrage, civil rights, LGBTQ+ equality all faced massive resistance until achieving tipping points where change accelerated. These suggest that transformation often involves long preparation followed by rapid shift once conditions align.

Yet research also documents how power adapts to preserve itself. Demands for change get absorbed, radical movements co-opted, structural reforms implemented in ways maintaining fundamental inequalities. The challenge is creating transformation that cannot be easily incorporated into existing power structures.

Prefigurative politics describes creating desired future in present through how movements organise themselves. Rather than accepting hierarchical organisation whilst fighting hierarchy, prefigurative approach models horizontal decision-making, consensual processes, and participatory structures. Research shows this builds capacity for alternative governance whilst demonstrating feasibility.

Studies of alternative economies, worker cooperatives, community land trusts, solidarity economy, time banking reveal functioning examples of different economic logics. These demonstrate that exchange, production, and distribution need not follow capitalist models. Research shows participants often experience increased wellbeing, autonomy, and meaning alongside economic benefits.

The possibility of transformation depends partly on crisis. Research shows that stable systems resist change whilst crises create openings for alternatives. Yet crises can produce reactionary responses as easily as progressive ones. What determines direction is which narratives, organisations, and practices are ready when openings appear.

Connection to previous chapters

This final chapter addresses what becomes possible after understanding all mechanisms examined throughout this book. Every previous chapter revealed how control operates; this chapter explores how communities heal from that control and build alternatives.

Consciousness (Chapter 2): Collective healing requires collective consciousness raising. Communities cannot address problems they cannot perceive. Shared awareness of systematic patterns enables coordinated response impossible when people experience problems as isolated failures.

Masks (Chapter 3): Healing requires dropping protective masks enough to encounter each other authentically. Community building depends on people revealing genuine struggles rather than performing competence. Vulnerability enables connection that masks prevent.

Crowds (Chapter 4): Collective healing mobilises crowd dynamics toward restoration rather than destruction. Shared emotional experience can support healing when channelled through appropriate structures providing safety and direction.

Indoctrination (Chapter 5): Healing from ideological trauma requires recognising how belief systems shaped perception. Communities recovering from authoritarian regimes, cults, or fundamentalism must address not just material damage but psychological conditioning requiring deprogramming.

Early belief systems (Chapter 6): Religious and spiritual practices offer resources for collective healing when deployed toward restoration rather than control. Rituals, ceremonies, and communal practices facilitate processing that secular approaches sometimes lack.

Capitalism (Chapter 7): Economic healing requires alternatives to market logic commodifying all relationships. Mutual aid, commons, and solidarity economies demonstrate that exchange need not follow capitalist patterns. Communities can organise care and production differently.

Hypernormalisation (Chapter 8): Collective healing begins when communities reject pretence that dysfunctional systems are normal. Naming contradictions, acknowledging failures, and refusing manufactured consent create space for imagining alternatives.

Control without violence (Chapter 9): Healing requires dismantling disciplinary structures internalised through surveillance and normalisation. Communities develop capacity for self-organisation without reproducing hierarchical control patterns.

Identity as weapon (Chapter 10): Collective healing addresses how identities have been weaponised to divide communities. Building solidarity across difference whilst honouring specific experiences requires nuanced approach avoiding both erasure and fragmentation.

Mental health (Chapter 11): Collective healing recognises that individual mental health problems often reflect collective dysfunction. Addressing root causes requires changing social conditions producing widespread distress rather than individualising systematic problems.

Education (Chapter 12): Healing educational systems means creating learning environments supporting development rather than compliance. Communities experiment with democratic schools, free schools, and alternative pedagogies demonstrating education need not be authoritarian.

Radicalisation (Chapter 13): Collective healing provides alternative to extremism's appeal. Communities offering belonging, meaning, and purpose reduce vulnerability to radical movements whilst helping people leave extremist groups through acceptance rather than punishment.

Individuality (Chapter 14): Collective healing supports individual autonomy rather than demanding conformity. Healthy communities value diverse perspectives and independent thinking as resources for collective wisdom rather than threats to unity.

Secular sacred (Chapter 15): Collective healing honours consciousness itself as sacred. Communities organise around protecting and nurturing conscious beings regardless of metaphysical beliefs, grounding ethics in reduction of suffering and enhancement of flourishing.

Algorithmic mind (Chapter 16): Healing from algorithmic manipulation requires communities reclaiming agency over attention and information. Digital commons, platform cooperatives, and community-controlled technology demonstrate alternatives to extractive platforms.

Economy of attention (Chapter 17): Collective healing protects communal attention from commercial extraction. Communities create spaces allowing sustained focus, deep conversation, and contemplative practice countering fragmentation economy imposes.

Story controls mind (Chapter 18): Collective healing involves creating new narratives about who communities are and what is possible. Storytelling serves crucial function in collective meaning-making, helping communities integrate trauma whilst imagining different futures.

Body remembers (Chapter 19): Collective healing addresses somatic dimension of trauma. Communities need embodied practices, movement, ritual, and somatic experiencing at collective level, not just individual therapy.

Courage to care (Chapter 20): Collective healing emerges from aggregated individual choices to care despite understanding systematic dysfunction. Each person choosing compassion over cynicism contributes to cultural shift enabling broader transformation.

Conclusion: the ongoing work

This book began by acknowledging that the world does not make sense, not because it is broken beyond repair but because much of what we are taught to believe about it is simplified, polished, and repeated until it feels natural. Twenty-one chapters later, that observation stands.

The opening scenario of neighbours gathering to address shared challenges illustrates collective healing operating practically. Nothing dramatic occurred: no revolution, no transformation of consciousness, merely people acknowledging mutual vulnerability and exploring cooperation. Yet such modest moments accumulate into cultural shifts.

This final chapter has examined what collective healing requires: acknowledging trauma rather than denying it, establishing shared truth despite contested narratives, creating accountability without pure punishment, building mutual aid networks demonstrating alternatives, using culture for processing and meaning-making, and imagining transformation whilst accepting uncertainty about outcomes.

Research presented throughout demonstrates that collective healing is possible but not inevitable. Truth and reconciliation processes sometimes facilitate healing, sometimes become politicised. Restorative justice can repair relationships or reinforce power imbalances. Mutual aid networks strengthen communities or remain marginal. Cultural practices enable processing or reinforce trauma.

What determines outcomes is not formulaic application of techniques but genuine commitment to healing over maintaining comfortable illusions or pursuing vengeance. Collective healing requires communities willing to acknowledge harm done and received, willing to sit with discomfort that acknowledgement produces, and willing to experiment with different ways of organising relationships.

This book has traced how consciousness is managed, how behaviour is directed, how belief is constructed, how control operates through crowds, indoctrination, capitalism, hypernormalisation, discipline, weaponised identity, pathologised distress, educational compliance, extremist capture, and eroded individuality.

It has shown how consciousness becomes sacred ground for ethical commitment, how algorithms exploit attention, how attention itself becomes commodified, how language shapes thought, how bodies encode experience, and how caring after disillusionment requires courage maintaining emotional engagement despite understanding manipulation.

Each chapter revealed mechanisms appearing natural or inevitable whilst demonstrating their constructed nature. Understanding construction does not automatically dismantle it. Systems persist through inertia, institutional reinforcement, and genuine difficulty imagining alternatives. Yet understanding creates possibility for choice where none existed.

The question facing anyone completing this journey through mechanisms of control is not whether systems will change but how to live consciously within them whilst building alternatives. This requires no illusions about ease or inevitability of transformation. It requires realistic assessment of difficulty alongside commitment to trying anyway.

Collective healing is not endpoint but ongoing practice. There is no moment when societies become whole and remain so. Each generation inherits both wisdom and wounds, adding its own. What matters is attention: societies noticing their own patterns possess chance to change them.

This book offers no final answers because consciousness does not evolve in straight lines. It advances, retreats, and recalibrates. What it offers instead are better questions: How do we live together without domination? How do we disagree without destruction? How do we care without illusion? These are not problems solved once but tensions held with maturity.

The work of being human is ongoing, cyclical, unfinished. Like garden requiring patience, humility, and care, collective wellbeing needs tending. Neglect allows patterns to return; vigilance allows balance to emerge. There is no permanent victory, only sustained presence.

What provides hope is not optimism but resilience. Humans continue creating meaning even when frameworks collapse. We continue reaching for connection despite repeated disappointments. We continue, against all evidence, to try again. This persistence suggests something fundamental about human nature resisting reduction to mere mechanism.

If this book has argued for anything, it is that responsibility does not end with disillusionment but deepens. To live without illusions is not to live without care. To see clearly is not to withdraw but to engage more honestly. Understanding manipulation does not require cynicism but enables mature compassion.

The future will not be saved by certainty nor destroyed by doubt. It will be shaped by those willing to remain awake: to feel, to question, to care, even when no authority commands it. This wakefulness represents not burden alone but capacity including awareness, perception, feeling, and choice.

Collective healing promises not perfect world but conscious one. Not society without conflict but one capable of navigating conflict without dehumanisation. Not elimination of suffering but honest acknowledgement of it alongside commitment to reduction where possible.

The quiet promise is this: communities can heal, alternatives can be built, transformation remains possible. Not guaranteed, not easy, not quick. But possible. And possibility is sufficient for action. The work does not require certainty about outcomes. It requires commitment to values regardless of guarantees.

This book has been attempt, not verdict. An effort to look clearly at how consciousness is shaped and controlled, knowing that clarity itself has limits. It offers no manifesto, no programme, no blueprint for perfect society. It offers only observation and invitation.

The observation: that systems shape us systematically whilst appearing natural, that understanding these systems changes everything and nothing, that collective healing is both necessary and difficult.

The invitation: to remain conscious, to question inherited narratives, to build alternative practices, to care despite understanding manipulation, to participate in collective healing however modestly, to choose being human over being machine.

What you do with this understanding is your choice. The mechanisms described operate whether acknowledged or not. But acknowledgement creates space where choice becomes possible. In that space lies whatever freedom remains: not freedom from conditioning but freedom to respond to it consciously.

The work continues. Communities gather, small practices accumulate, alternatives emerge. Not revolution but evolution. Not certainty but commitment. Not perfection but presence. This is the long work of being human together.

As I see it, that is the quiet promise of collective healing: not that the world will be fixed, but that we can remain awake to it, engaged with it, and capable of caring for each other within it. That, perhaps, is enough.

End of Chapter 21

End of As I See It