As I See It

Vayu Putra

Chapter 18

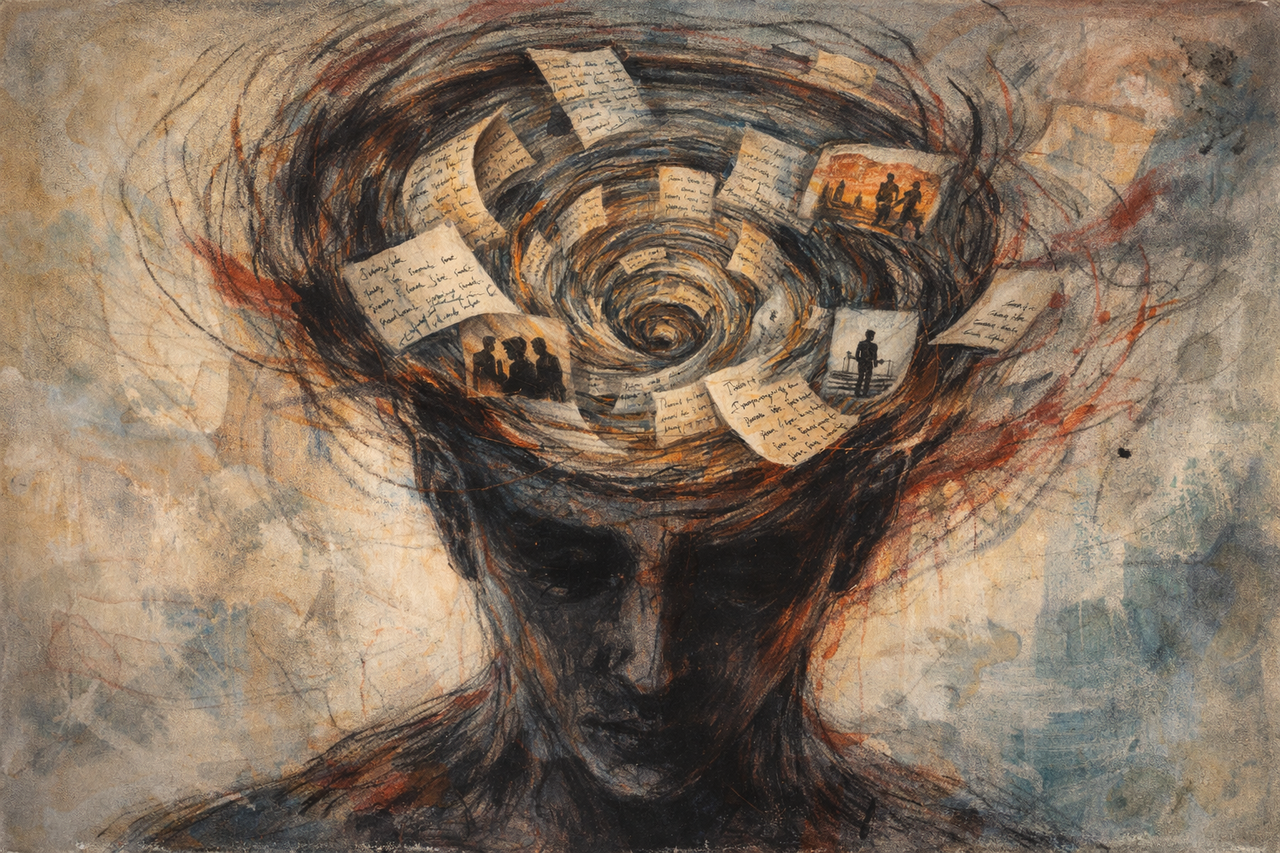

The Story Controls the Mind

You are reading news coverage of an economic policy when you notice the language choices: "Reform" rather than "cuts." "Flexibility" rather than "deregulation." "Growth" rather than "inequality."

Each word frames the policy positively whilst obscuring potential harms. The article never explicitly advocates for the policy, yet the language does the persuasion invisibly. You find yourself nodding along, thinking "reform sounds reasonable," without examining what is actually being reformed or whom the changes will benefit and harm.

This is not accidental but deliberate framing. Political language rarely describes neutrally. It frames issues through metaphors, euphemisms, and loaded terms that pre-emptively shape judgement. "Tax relief" assumes taxes are burden. "Pro-life" claims moral high ground through naming. "Free market" suggests liberty rather than economic system. The terminology determines the debate before arguments begin.

Language is not transparent window onto reality but active constructor of it. The words available shape what can be thought. The metaphors used determine what seems natural. The narratives told become the reality experienced. This makes language fundamental instrument of power: whoever controls the words controls the thoughts those words enable or prevent.

This chapter examines how language shapes thought, why certain linguistic frames dominate discourse, what research reveals about narrative's power over reason, how political and corporate language manipulates through systematic techniques, and why linguistic precision represents crucial form of cognitive resistance.

Language shapes thought

The relationship between language and thought has occupied linguists, psychologists, and philosophers for centuries. Whilst extreme versions of linguistic determinism prove untenable, substantial evidence shows that language significantly influences cognition, perception, and behaviour.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, articulated by linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf in early 20th century, proposed that language structure determines thought patterns. Whorf's research on Hopi language suggested speakers conceived time differently than English speakers due to linguistic differences. Whilst his strongest claims proved incorrect, the weaker version, linguistic relativity, gains empirical support.

Psychologist Lera Boroditsky's research demonstrates language's cognitive effects across domains. Russian speakers, whose language obligatorily marks gender on nouns, show different patterns of gender association than English speakers. Speakers of languages encoding absolute direction (north, south, east, west) rather than relative direction (left, right) maintain constant awareness of cardinal orientation, demonstrating language affecting basic spatial cognition.

Research on colour perception shows that languages carving colour spectrum differently affect colour discrimination and memory. Studies comparing speakers of languages with many versus few colour terms find measurable differences in perceptual boundaries and recall, suggesting language influences even basic perception.

Grammatical gender affects cognition beyond grammar. Research shows that speakers of gendered languages attribute stereotypically masculine or feminine properties to objects based on grammatical gender rather than inherent properties. A bridge described with masculine gender in German and feminine gender in Spanish leads speakers to generate different associations.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman's research on framing effects demonstrates how presenting identical information differently produces dramatically different judgements. Medical treatments described as "90% survival rate" versus "10% mortality rate" generate different patient choices despite mathematical equivalence. Language framing shapes decisions about risk, morality, and policy.

The implications extend to abstract thinking. Research shows that using precise language for emotions improves emotional regulation. Studies comparing individuals with high versus low emotional granularity (ability to distinguish finely between emotional states) find that those with richer emotional vocabulary experience better mental health and adaptive coping.

Orwell and political language

George Orwell's essay "Politics and the English Language" (1946) remains definitive analysis of how political language corrupts thought. Orwell argued that unclear language enables dishonest thinking, and dishonest thinking produces unclear language in self-reinforcing cycle degrading both politics and minds.

His primary targets were euphemism, vagueness, and ready-made phrases that substitute for original thought. Political language, Orwell observed, "is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind." When describing atrocities, political language employs abstractions divorcing words from reality.

Examples from Orwell's era include "pacification" for bombing villages, "liquidation" for mass murder, "rectification of frontiers" for ethnic cleansing. Contemporary equivalents proliferate: "enhanced interrogation" for torture, "collateral damage" for civilian casualties, "extraordinary rendition" for kidnapping, "negative patient outcome" for death. Each euphemism distances speaker and audience from reality.

In "Nineteen Eighty-Four" (1949), Orwell invented Newspeak, fictional language where reduced vocabulary makes certain thoughts literally unthinkable. Whilst totalitarian parody, Newspeak illustrates real phenomenon: when language lacks words for concepts, those concepts become difficult to articulate and therefore to defend politically.

Research on Newspeak's linguistic principles shows that whilst language does not absolutely determine thought, restricted vocabulary impairs complex reasoning about restricted domains. Studies comparing individuals with rich versus limited political vocabulary find significant differences in political sophistication and ability to critique power.

Orwell's solution was linguistic honesty: preferring concrete over abstract language, favouring active over passive voice, choosing short words over long, eliminating unnecessary words, and breaking any rule rather than saying something outright barbarous. These principles remain relevant for resisting linguistic manipulation.

Political scientist Murray Edelman's "Political Language" (1977) extended Orwell's analysis, showing how political discourse uses ambiguity strategically. Vague terms like "national security," "public interest," and "economic growth" mean different things to different audiences, allowing politicians to appear agreeable to all whilst committing to nothing specific.

Framing and metaphor

Linguist George Lakoff's research on framing demonstrates that political battles are fundamentally battles over metaphor. How issues are framed determines what solutions seem reasonable. The terminology chosen activates mental frameworks shaping subsequent reasoning unconsciously.

Lakoff's analysis of "tax relief" exemplifies framing's power. The metaphor embeds assumption that taxes are affliction requiring relief. This frame makes tax reduction seem obviously good, tax increases obviously harmful. Alternative frames, "tax investment" or "membership fees," would activate different conceptual systems producing different judgements.

Research on metaphor shows it is not mere rhetorical flourish but fundamental cognitive process. People reason about abstract concepts through concrete metaphors. Lakoff and philosopher Mark Johnson's "Metaphors We Live By" (1980) catalogues how metaphors structure thought unconsciously: time is money, argument is war, understanding is seeing, life is journey.

These metaphors are not arbitrary. Research shows that activating specific metaphors measurably affects judgement. Studies where crime is described as "beast" versus "virus" find that participants recommend different solutions: punishment versus treatment. The metaphor frames the problem, which determines what counts as solution.

Political frames operate through moral frameworks. Lakoff identifies "strict father" versus "nurturant parent" as organising metaphors for conservative versus progressive politics. Each metaphor generates entire policy positions through logical extension. Understanding this reveals why factual arguments often fail: they address surface positions whilst leaving underlying frames intact.

Research on reframing shows changing metaphors changes minds. Public health campaigns reframing obesity from individual moral failing to systemic problem reduce stigma and increase support for policy interventions. Environmental campaigns reframing climate change from distant threat to present danger increase concern and action intention.

The implication is that political persuasion requires not just better arguments but better frames. Progressives often accept conservative frames whilst arguing against conclusions. This concedes rhetorical territory making persuasion nearly impossible. Effective resistance requires establishing alternative frames that activate different moral frameworks.

Manufacturing consent through repetition

Linguist Noam Chomsky and economist Edward Herman's "Manufacturing Consent" (1988) analysed how mass media serve elite interests through systematic propaganda. The model does not require conspiracy but operates through institutional structures and economic incentives producing conformity to dominant narratives.

The propaganda model identifies five filters shaping news: media ownership by large corporations, advertising as primary revenue source, reliance on government and corporate sources, flak discouraging inconvenient reporting, and anti-communist ideology as control mechanism. These filters systematically exclude information threatening elite interests whilst amplifying information supporting them.

Research testing the propaganda model finds substantial support. Studies comparing media coverage of similar atrocities show dramatically different framing depending on whether perpetrators are allies or adversaries. Violence by official enemies receives extensive sympathetic coverage; comparable violence by allies receives minimal critical coverage.

Repetition transforms lies into truth through familiarity. Psychologist Daniel Kahneman documents "availability heuristic" where frequency of exposure affects perceived probability. Information encountered repeatedly feels more true regardless of accuracy. This makes repetition itself persuasive independent of content.

Research on illusory truth effect demonstrates this mechanism. Studies showing participants false statements find that mere repetition increases perceived truth. Even when participants know statements are false, repetition makes them feel more true. This operates unconsciously: people cannot resist the effect even when aware of it.

Modern propaganda exploits these mechanisms systematically. Political slogans repeat simple phrases until they become reflexive. "Strong and stable," "Make America great again," "Take back control" function through repetition creating familiarity that bypasses critical thinking. The content matters less than rhythmic memorability.

Social media amplifies repetition effects through viral spread and algorithmic recommendation. Research shows that false information spreads faster than truth on social media because novelty and emotional intensity drive sharing. Once false claims achieve critical mass of repetition, corrections struggle to counteract familiarity advantage.

Myth and national narrative

Political scientist Benedict Anderson's "Imagined Communities" (1983) analysed how nations are "imagined" into existence through shared narratives. Nations are not natural entities but socially constructed through print capitalism, vernacular languages, and collective myths creating sense of horizontal solidarity amongst strangers.

National narratives operate through what Anderson calls "deep, horizontal comradeship" making people willing to die for abstractions. This requires myths establishing ancient origins, shared destiny, and unique character. National histories are selectively told, emphasising glories whilst minimising atrocities, creating sanitised pasts supporting present political arrangements.

Historian Eric Hobsbawm's "The Invention of Tradition" (1983) documented how supposedly ancient national traditions were often recently fabricated. Scottish tartans, British royal ceremonies, and various "timeless" cultural practices were invented in 18th and 19th centuries to legitimate contemporary power structures through mythical continuity with invented pasts.

French philosopher Ernest Renan argued in "What is a Nation?" (1882) that nations are constituted through collective amnesia as much as collective memory. National identity requires forgetting inconvenient historical facts, particularly founding violences and internal diversities threatening unity narratives. "Forgetting," Renan wrote, "is a crucial factor in the creation of a nation."

American exceptionalism exemplifies national mythology. The narrative of America as uniquely free, democratic, and virtuous requires systematically forgetting genocide of indigenous peoples, centuries of slavery, imperialism, and ongoing racial injustice. School curricula, political rhetoric, and popular culture constantly reproduce sanitised versions emphasising founding principles whilst minimising founding crimes.

British imperialism similarly deployed mythological narratives. The "civilising mission" framed colonial conquest as benevolent intervention spreading civilization, Christianity, and commerce. This narrative persists in contemporary nostalgia for empire despite historical reality of exploitation, violence, and cultural destruction imposed on colonised peoples.

Research on collective memory shows nations actively construct pasts through education, commemoration, and media. Studies comparing history textbooks across countries reveal dramatically different narratives of shared events. Wars appear as heroic defences in victor nations, tragic losses in defeated nations. Colonial history appears as development in former colonisers, exploitation in formerly colonised.

Corporate language and branding

Corporate language operates through similar mechanisms as political language but with explicitly commercial purposes. Marketing converts products into identities, consumption into values, and brands into belief systems through carefully constructed linguistic associations.

Cultural critic Naomi Klein's "No Logo" (2000) analysed how branding transcends product quality to sell lifestyles and identities. Nike sells not shoes but athleticism and determination. Apple sells not computers but creativity and innovation. Brands become shorthand for values that consumers purchase to express identity through consumption.

Research on brand loyalty shows it operates psychologically similarly to religious or political identity. Brain imaging reveals that favourite brands activate same regions as religious or political symbols. People defend preferred brands against criticism with emotional intensity disproportionate to actual product differences, suggesting branding succeeds in converting commercial into identity relationships.

Corporate euphemisms obscure exploitative practices through linguistic sanitisation. "Human resources" reduces people to assets. "Downsizing" or "rightsizing" masks mass firings. "Flexible working" conceals precarity. "Sharing economy" disguises casualised labour. Each term reframes exploitation as progress or necessity.

Workplace jargon creates hierarchies through linguistic exclusion. Management speak, corporate buzzwords, and industry-specific terminology function as shibboleths distinguishing insiders from outsiders. Research shows that jargon serves primarily to signal group membership and status rather than improve communication clarity.

Advertising language exploits psychological vulnerabilities systematically. Research on marketing psychology documents techniques including scarcity appeals ("limited time offer"), social proof ("everyone is buying"), authority endorsement, and emotional association. These bypass rational evaluation by triggering automatic responses.

Philosopher Herbert Marcuse argued in "One-Dimensional Man" (1964) that advertising language creates false needs, transforming wants into necessities through repetition and association. What begins as luxury becomes essential through linguistic redefinition supported by constant exposure creating new baselines for normal consumption.

Narrative transportation and persuasion

Psychological research on narrative transportation demonstrates that stories persuade more effectively than arguments. When people become absorbed in narratives, they experience reduced counterarguing and increased identification with characters, making narrative persuasion particularly powerful.

Psychologists Melanie Green and Timothy Brock's research shows that narrative engagement predicts belief change independent of argument quality. Well-crafted stories change attitudes even when containing weak arguments, whilst strong arguments in non-narrative form often fail to persuade. This occurs because narratives bypass critical evaluation through emotional engagement.

Neuroscience research on story comprehension reveals why narratives prove so persuasive. Brain imaging shows that reading stories activates not just language regions but sensory, motor, and emotional networks simulating described experiences. This creates vicarious experience that feels authentic, making narrative claims seem self-evidently true.

Research comparing fact-based versus narrative health communications consistently finds narrative superiority. Public health campaigns using personal stories generate more attitude change and behaviour modification than statistical evidence, even when statistics are more compelling objectively. Stories feel real in ways data cannot match.

This creates vulnerability to manipulation through anecdote. Single compelling story outweighs statistical trends in subjective impact. Research shows people judge risk based on memorable examples rather than base rates. Media coverage amplifying rare but dramatic events (terrorism, violent crime) whilst ignoring common but undramatic threats (heart disease, car accidents) produces distorted risk perceptions.

Political narratives exploit transportation effects systematically. Campaign advertisements tell stories of sympathetic individuals to generate emotional responses circumventing policy analysis. "Welfare queen" narratives, despite being statistically insignificant, shape public opinion about social programmes through memorable anecdotes that feel representative.

Historian Hayden White's analysis of historical narrative shows that even factual histories operate through narrative structures borrowed from literature. How events are emplotted, which genre conventions are employed, and what moral frameworks are applied all shape interpretation of historical facts. History is not merely discovered but narratively constructed.

Linguistic resistance and clarity

If language shapes thought and narrative controls perception, linguistic precision becomes form of resistance. Speaking and writing clearly, refusing euphemism, and questioning frames all represent practices reclaiming cognitive autonomy from linguistic manipulation.

Orwell's principles for clear writing remain relevant: prefer concrete language over abstract, favour active voice over passive, choose short familiar words over long obscure ones, cut unnecessary words, and break any rule rather than say something barbarous. These guidelines resist linguistic manipulation by maintaining connection between words and reality.

Research on critical language awareness shows that teaching people to analyse political and advertising language improves resistance to manipulation. Studies where students learn to identify framing, metaphor, and euphemism find increased scepticism towards propaganda and better ability to evaluate claims independently of linguistic packaging.

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein argued that philosophical problems often arise from linguistic confusion. His late work emphasised examining language in use, questioning assumptions embedded in grammar and ordinary speech. This approach, applied to political language, reveals how problems are linguistically constructed and might be linguistically dissolved.

Feminist linguistics demonstrates how gendered language encodes and perpetuates sexism. Research shows that "generic masculine" (using "he" and "man" for all genders) actually activates male imagery rather than generic human imagery. Language reform introducing gender-neutral terms measurably affects gender attitudes and stereotyping.

Critical race theorists analyse how racial language constructs racial categories as natural rather than socially constructed. The vocabulary available for discussing race shapes what racial analyses seem possible. Developing alternative linguistic frameworks enables thinking about race differently, potentially undermining racism's linguistic foundations.

Poet and essayist Adrienne Rich's concept of "language as false naming" describes how dominant language distorts women's experiences. Reclaiming language involves both resisting misnamings and creating new terms capturing experiences previously unnamed. This applies broadly: marginalised groups develop language resisting dominant narratives erasing or distorting their realities.

Connection to previous chapters

Language operates as fundamental medium through which all previous mechanisms function. Every form of control, manipulation, and resistance examined throughout this book operates through linguistic framing.

Consciousness (Chapter 2): Language shapes what consciousness can attend to by determining what can be named and thought. The burden of consciousness includes awareness that language structures awareness itself, creating recursive loop where thinking about thought requires linguistic categories that shape the thinking.

Masks (Chapter 3): Social roles are linguistically constructed through titles, scripts, and narratives defining appropriate behaviour. Learning to perform masks involves acquiring language appropriate to each role, internalising linguistic patterns that shape self-presentation.

Crowds (Chapter 4): Crowd formation depends on shared language creating collective identity. Slogans, chants, and rhetorical appeals mobilise crowds by establishing linguistic frames unifying disparate individuals into collective subjects.

Indoctrination (Chapter 5): Indoctrination operates primarily through language, teaching specific vocabularies, metaphors, and narratives that structure thought within ideological boundaries. Successful indoctrination makes certain thoughts literally unsayable within available linguistic resources.

Early belief systems (Chapter 6): Religious and cultural belief systems transmit through language: sacred texts, ritual speech, theological vocabulary. Learning belief systems means acquiring linguistic frameworks structuring religious experience and moral reasoning.

Capitalism (Chapter 7): Economic systems require linguistic frameworks naturalising market relations. Terms like "labour market," "human capital," and "economic growth" frame capitalism as natural rather than historically contingent, making alternatives seem unrealistic through linguistic constraints.

Hypernormalisation (Chapter 8): The gap between official narratives and lived reality requires language maintaining both simultaneously. Euphemism, doublespeak, and corporate speak enable describing dysfunctional systems as functional, creating linguistic hypernormalisation matching material conditions.

Control without violence (Chapter 9): Linguistic control operates subtly by shaping available concepts rather than prohibiting specific speech. When language itself frames compliance as freedom and resistance as irrationality, violence becomes unnecessary because thought police themselves.

Identity as weapon (Chapter 10): Identity politics operates through linguistic construction of group boundaries. Who counts as "us" versus "them" depends on linguistic categories that appear natural but are socially constructed and politically deployed.

Mental health (Chapter 11): Diagnostic language shapes how mental distress is understood and treated. Whether suffering is framed as individual pathology or systemic response determines interventions. Language medicalising normal responses to abnormal conditions serves pharmaceutical and social control interests.

Education (Chapter 12): Educational language frames learning as training, students as human capital, and teaching as delivering content. This vocabulary naturalises education serving economic rather than humanistic purposes, making alternative visions difficult to articulate within dominant discourse.

Radicalisation (Chapter 13): Extremist narratives provide linguistic frameworks transforming grievances into absolutes. Radical movements offer comprehensive explanatory vocabularies making complex problems appear simply solvable through total commitment to movement's vision.

Individuality (Chapter 14): Independent thought requires linguistic resources expressing perspectives unsupported by dominant discourse. Maintaining individuality means refusing to think entirely within provided vocabulary, developing language for experiences and ideas mainstream narratives obscure.

Secular sacred (Chapter 15): Ethical frameworks require language articulating values transcending utilitarian calculation. Secular sacred depends on linguistic precision distinguishing genuine moral concerns from instrumental rationalisations disguised as ethics.

Algorithmic mind (Chapter 16): Algorithms optimise engagement through linguistic framing: headlines, notifications, recommendations all use language engineered to capture attention. The vocabulary of platform capitalism, "likes," "followers," "engagement," frames social relations as metrics.

Economy of attention (Chapter 17): Attention economy operates through linguistic fragmentation: headlines over articles, slogans over arguments, memes over essays. The compression of language matches compression of attention, creating feedback loop where both become increasingly fragmented.

Conclusion: reclaiming linguistic autonomy

This chapter has documented how language shapes thought, why certain linguistic frames dominate discourse, what research reveals about narrative's persuasive power, how political and corporate language manipulates systematically, and why linguistic precision represents crucial cognitive resistance.

The research presented demonstrates that whilst language does not absolutely determine thought, it profoundly influences cognition through multiple mechanisms. Linguistic relativity research shows that language structure affects perception, memory, and reasoning. Framing research demonstrates that identical information produces different judgements depending on linguistic presentation.

Political language exploits these effects through euphemism, abstraction, and ready-made phrases corrupting thought. Orwell's analysis remains accurate: unclear language enables dishonest thinking. Contemporary examples from "collateral damage" to "enhanced interrogation" show how euphemism distances people from reality, making atrocity administrable.

Framing research reveals that political battles are fundamentally battles over metaphor. Lakoff's work shows that terminology activates conceptual frameworks determining what solutions seem reasonable. "Tax relief" versus "tax investment" activates different moral reasoning producing different policy preferences through linguistic choice alone.

Manufacturing consent operates through systematic repetition making lies feel true through familiarity. Chomsky and Herman's propaganda model shows how institutional structures produce conformity to dominant narratives without requiring conspiracy. Research on illusory truth effect confirms that repetition increases perceived accuracy regardless of actual truth.

National narratives construct imagined communities through selective histories emphasising glories whilst minimising atrocities. Anderson, Hobsbawm, and Renan demonstrate how nations are linguistically imagined into existence through myths requiring both remembering and forgetting. National identity depends on narratives obscuring inconvenient truths.

Corporate language converts products into identities and consumption into values through branding creating belief systems. Research shows brand loyalty activates same neural regions as religious or political identity. Workplace euphemisms obscure exploitation: "human resources," "downsizing," "flexibility" linguistically sanitise dehumanisation, firings, and precarity.

Narrative transportation research reveals why stories persuade more effectively than arguments. Well-crafted narratives bypass critical evaluation through emotional engagement, making narrative claims seem self-evidently true. This creates vulnerability to manipulation through anecdote outweighing statistical evidence in subjective impact.

Yet linguistic resistance remains possible through clarity, precision, and critical awareness. Orwell's principles for clear writing, critical language education, and feminist and anti-racist linguistic interventions all demonstrate that analysing and reforming language can challenge dominant frames and enable alternative thinking.

The opening scenario of reading policy coverage illustrates linguistic framing operating practically. "Reform" sounds positive regardless of what is reformed. "Flexibility" suggests benefit regardless of whose interests it serves. The terminology pre-emptively shapes judgement, making linguistic choices political acts.

What makes linguistic control particularly effective is its invisibility. People experience language as transparent medium rather than active constructor of reality. This naturalness makes linguistic framing operate unconsciously, shaping thought without awareness that thinking is being shaped.

The chapter argues that whoever controls language controls thought through framing what can be said, imagined, and therefore done. Political, corporate, and cultural power operates substantially through linguistic domination establishing vocabulary, metaphors, and narratives that structure collective consciousness.

Reclaiming linguistic autonomy requires deliberate practices: questioning frames, refusing euphemisms, demanding clarity, developing alternative vocabularies, and maintaining awareness that language is never neutral. Every linguistic choice either reinforces or challenges dominant narratives.

The secular sacred framework provides ethical foundation for linguistic resistance: if consciousness is sacred, and language shapes consciousness, then linguistic manipulation violates fundamental ethical commitment to protect conscious experience. Truthful speech becomes ethical obligation, whilst deceptive language becomes violence against consciousness.

Linguistic control operates as fundamental mechanism underlying all others examined throughout this book. Consciousness, identity, belief, economic systems, political arrangements, technological interfaces all depend on linguistic frameworks determining what can be thought. Language is not merely tool for expressing pre-existing thoughts but active constructor of what thoughts are possible.

Whether societies can resist linguistic manipulation whilst embedded in institutions systematically deploying it remains uncertain. The forces promoting euphemism, framing, and narrative control are powerful, sophisticated, and mostly invisible. Yet awareness of these dynamics creates possibility for resistance through conscious linguistic choices.

In world where language shapes reality, speaking truthfully becomes revolutionary act. Refusing euphemisms that obscure violence, questioning frames that pre-determine judgements, and demanding linguistic clarity that reconnects words with reality all represent crucial practices for maintaining cognitive autonomy against systems designed to capture thought through capturing language.

The story controls the mind only when the mind fails to recognise it is story. Awareness that narratives are constructed rather than discovered, that frames are chosen rather than natural, and that language shapes thought rather than merely expressing it creates possibility for linguistic resistance. This awareness, combined with deliberate practice choosing words carefully, represents fundamental defence of consciousness against linguistic colonisation.

End of Chapter 18