As I See It

Vayu Putra

Chapter 20

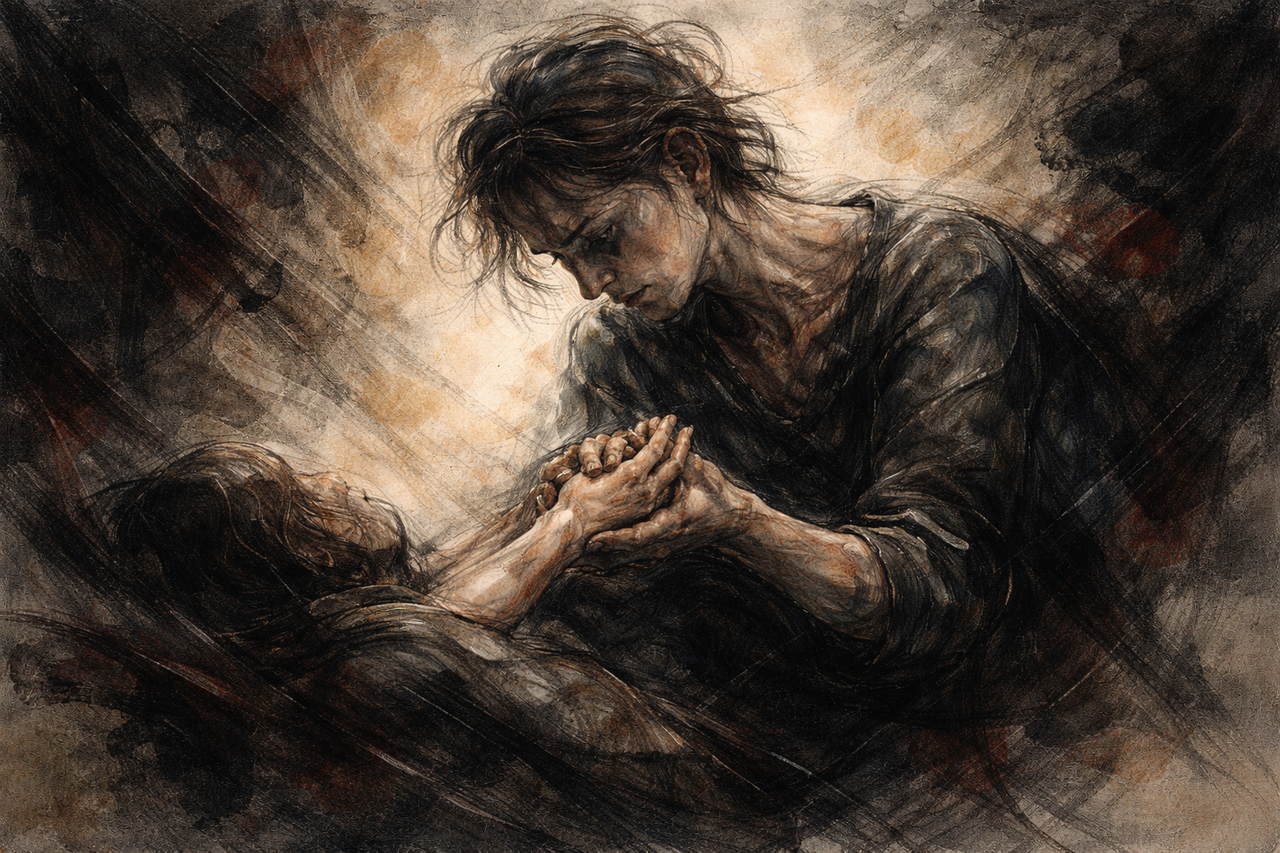

The Courage to Care

You are scrolling through news of another disaster when you notice yourself feeling nothing.

The images are horrific: conflict, displacement, suffering on scales difficult to comprehend. Yet you register them with the same emotional flatness as advertisements or weather reports. You continue scrolling. Another tragedy appears. You scroll past that too. The numbness is not deliberate; it simply is.

Later, discussing current events with colleagues, you find yourself deploying cynical commentary. Nothing surprises you anymore. Every development fits familiar patterns of power, manipulation, and predictable human failure. Your analysis is sharp, your detachment complete. Someone suggests action; you explain why it will not work. Someone expresses hope; you enumerate why it is misplaced.

This posture feels like wisdom. After learning how systems operate, how narratives construct reality, how power perpetuates itself despite appearing to change, caring seems naïve. Emotional investment appears foolish when outcomes seem predetermined. Cynicism offers protection: if nothing matters, nothing can disappoint.

Yet something about this stance feels incomplete. The numbness that protects also isolates. The detachment that prevents disappointment also prevents connection. You have learned to see through illusions but find yourself standing nowhere, committed to nothing, caring about less and less whilst claiming to understand more and more.

This chapter examines what happens after disillusionment, why cynicism represents incomplete liberation, what research reveals about compassion and moral engagement, how caring survives knowledge of systemic failure, and why maintaining the capacity to care represents crucial resistance to forces benefiting from apathy.

The psychology of cynicism

Cynicism often arrives disguised as intelligence. After belief systems reveal their machinery, after institutions expose their compromises, the temptation is not ignorance but indifference. Detachment masquerades as clarity, emotional distance as realism, withdrawal as wisdom.

Research distinguishes between healthy scepticism and corrosive cynicism. Scepticism maintains capacity for trust whilst demanding evidence. Cynicism assumes distrust as default, interpreting all actions through lens of self-interest and manipulation. Studies show that highly cynical individuals experience worse health outcomes, lower income, increased stress, and reduced life satisfaction.

The psychological function of cynicism is self-protection. When repeated disappointments, betrayals, or revelations of systematic deception accumulate, cynicism provides emotional armour. By expecting the worst, people avoid being hurt by it. By trusting nothing, they cannot be betrayed. This defensive posture feels rational given evidence of pervasive manipulation.

Yet cynicism exacts costs often invisible to those employing it. Studies on emotional numbing show that suppressing one emotion dampens capacity to feel others. People protecting themselves from disappointment simultaneously reduce access to joy, wonder, and connection. The armour that prevents pain also prevents aliveness.

Cynicism creates self-fulfilling prophecy. Expecting self-interest in others, cynics behave self-interestedly, producing environments where cynicism appears justified. Research shows that cynical individuals are more likely to lie, cheat, and exploit others, then interpret others' defensive responses as confirming their worldview. The cycle perpetuates.

Brain imaging studies reveal that chronic cynicism affects neural processing. Cynical individuals show reduced activity in brain regions supporting empathy and social connection whilst showing increased activity in regions associated with threat detection and negative evaluation. The brain physically reorganises around defensive interpretation.

This represents one of power's subtler victories. When systems cannot command belief, they encourage apathy. When obedience fails, disengagement succeeds. A population that no longer cares is easier to manage than one believing passionately in alternatives. Cynicism immobilises whilst appearing sophisticated.

Compassion fatigue and emotional numbing

Compassion fatigue describes state where capacity for empathy depletes through overwhelming exposure to suffering. Originally identified in healthcare workers and humanitarian aid staff, the phenomenon has expanded with digital media making global suffering continuously visible.

Studies of compassion fatigue show predictable patterns: initial empathic response followed by gradual numbing, increased cynicism about helping, emotional detachment, reduced sense of personal accomplishment, and eventual burnout. These symptoms mirror post-traumatic stress, suggesting that witnessing suffering creates similar physiological impacts as experiencing trauma directly.

The volume of suffering presented through news and social media exceeds human capacity for emotional processing. Research on "psychic numbing" demonstrates that people struggle to feel proportionate concern as numbers increase. One child suffering registers emotionally; thousands suffering becomes statistic. The mind cannot maintain empathic engagement at scale.

This creates moral paradox. The more connected we become to global suffering, the more we must numb ourselves to function. Constant exposure produces desensitisation as adaptive response. People scroll past atrocities with same emotional registration as mundane updates because sustaining appropriate emotional response to each would paralyse daily functioning.

Research on emotional regulation shows two primary strategies: reappraisal (changing interpretation of situation) and suppression (inhibiting emotional expression). Chronic use of suppression correlates with worse psychological outcomes, whilst reappraisal generally proves healthier. Yet when confronting systematic suffering without clear action pathways, even reappraisal offers limited relief.

The phenomenon extends beyond individual psychology to social level. Societies experiencing prolonged crisis develop collective numbing. Research on populations living through wars, economic collapse, or systematic oppression shows normalisation of conditions that would provoke outrage in stable contexts. Atrocity becomes background, suffering routine.

This raises difficult question: how to maintain emotional responsiveness without being overwhelmed? Studies suggest that sustainable compassion requires boundaries, self-care, and connection to effective action. Empathy disconnected from agency produces paralysis. Caring linked to meaningful response, however small, sustains engagement.

The science of compassion

Compassion is not mere sentiment but trainable capacity with measurable neural correlates. Brain imaging studies show that compassion activates distinct networks from empathy alone. Empathy involves sharing others' emotional states; compassion adds motivational component directed toward relieving suffering.

Research comparing empathy with compassion reveals important distinction. Empathic distress, feeling others' pain intensely, often leads to personal distress and withdrawal. Compassion, characterised by concern and care without overwhelming identification, proves more sustainable. Studies show that compassion training reduces burnout in caregiving professions whilst empathy training without compassion component sometimes increases distress.

Loving-kindness meditation, practice of cultivating compassion through directed well-wishing, produces measurable changes. Regular practitioners show increased positive emotions, social connection, physical health, and life satisfaction. Brain imaging reveals enhanced activity in regions supporting empathy and emotion regulation, along with increased vagal tone indicating improved stress resilience.

Studies on altruism reveal that helping others activates brain reward centres, suggesting compassionate action is intrinsically reinforcing. This contradicts assumptions that humans are fundamentally selfish. Whilst self-interest motivates much behaviour, capacity for genuine concern for others appears equally fundamental to human nature.

Research on moral emotions shows that compassion operates alongside justice concerns. People can simultaneously care about individuals whilst demanding systemic change. These are not contradictory but complementary. Compassion without justice concerns can enable exploitation; justice without compassion can become punitive.

Importantly, compassion does not require naïveté. Studies show that compassionate individuals are not less aware of threat or deception but process threat differently. Rather than responding with defensive closure, they maintain openness whilst taking appropriate protective action. Compassion grounded in clear perception proves more effective than compassion based on denial.

This suggests that caring after disillusionment represents maturation rather than regression. Naïve compassion believes suffering can be easily resolved. Mature compassion acknowledges complexity whilst refusing to let complexity become excuse for indifference. It cares precisely because suffering persists, not despite it.

In-group bias and moral exclusion

Human compassion typically operates within boundaries. Research on in-group bias demonstrates that people automatically favour those perceived as similar: same race, nationality, religion, political affiliation, or even arbitrary group assignments in laboratory studies. This bias operates largely unconsciously, affecting resource allocation, empathic response, and moral consideration.

Brain imaging studies show that observing in-group members in pain activates empathy networks more strongly than observing out-group members. This neural favouritism operates automatically, occurring within milliseconds of perceiving group membership. The brain literally feels others' pain differently based on perceived similarity.

Moral exclusion describes process whereby certain individuals or groups fall outside boundaries of moral consideration. Research shows that people excluded from moral community are perceived as less human, their suffering less important, their rights less sacred. This dehumanisation enables atrocities that would be unthinkable if victims were perceived as fully human.

Studies on moral circles reveal variable boundaries of concern. Some people extend moral consideration only to immediate family; others include community, nation, all humans, animals, or entire ecosystems. These circles can expand or contract based on perceived threat, resource scarcity, or ideological framing.

Political polarisation demonstrates moral exclusion operating within societies. Research shows that people increasingly view opposing partisans as immoral, unintelligent, and dangerous. This perception justifies dismissing their concerns, celebrating their misfortunes, and supporting policies harming them. The out-group stops being fellow citizens deserving consideration and becomes enemy deserving defeat.

Tribal loyalty simplifies moral landscape by limiting compassion to those already aligned. Systems of power exploit this tendency systematically. By strengthening group boundaries and emphasising threats from outsiders, they redirect compassion inward whilst legitimising indifference or hostility outward.

Yet research also demonstrates that moral circles can expand. Perspective-taking exercises, personal relationships crossing group boundaries, and narratives highlighting common humanity all reduce bias. Importantly, expanding moral concern does not require abandoning group identity but rather recognising that multiple identities coexist and shared humanity transcends specific affiliations.

Vulnerability and strength

Vulnerability is widely misunderstood as weakness when it actually represents fundamental human capacity requiring courage to express. Research on vulnerability shows that willingness to be seen, to risk rejection, to acknowledge uncertainty proves essential for authentic connection and psychological health.

Studies on emotional expression demonstrate that suppressing vulnerability requires constant energy and produces negative health outcomes. People hiding vulnerability show elevated stress hormones, reduced immune function, and increased risk of psychological disorders. Paradoxically, the armour people construct for protection becomes source of suffering.

Research on relationships reveals that vulnerability enables intimacy. Sharing authentic feelings, admitting mistakes, expressing needs all create opportunities for genuine connection. Relationships built on invulnerability remain superficial because people never encounter each other truthfully. The persona connects but the person remains isolated.

Leadership research challenges assumptions that vulnerability undermines authority. Studies show that leaders who acknowledge uncertainty, admit errors, and express appropriate emotion actually increase trust and team performance. Invulnerability creates distance; vulnerability creates connection that enhances influence.

The cultural devaluation of vulnerability, particularly for men, produces widespread emotional illiteracy and isolation. Research shows that men socialised to suppress vulnerability experience higher rates of substance abuse, violence, and suicide. The demand for invulnerability literally kills people whilst appearing to make them strong.

Choosing vulnerability represents resistance to social conditioning demanding emotional suppression. Societies train people systematically to harden: children learn which feelings are acceptable, sensitivity gets corrected, vulnerability becomes managed. By adulthood, many cannot access emotional range necessary for authentic living.

Yet vulnerability chosen consciously differs from vulnerability imposed. Choosing to remain open whilst aware of danger requires strength impossible for those who have never confronted their own defensiveness. This is not naïveté but courage: maintaining softness in world rewarding hardness, staying present to pain rather than numbing.

The responsibility to feel

Awareness brings responsibility that cannot be delegated. Once systems of exploitation, manipulation, and systematic harm become visible, claiming innocence through ignorance becomes impossible. Nor can people retreat into detachment without consequence. To be conscious is to be implicated.

This makes feeling itself a moral act. Not indulgent emotionality but attentive presence to what is actually occurring. Allowing oneself to feel sorrow without rushing to resolve it. Staying with discomfort rather than escaping into analysis or outrage. This contradicts culture valuing reaction over reflection and certainty over sensitivity.

Research on moral emotions shows that emotional responses guide ethical behaviour more than abstract reasoning. Feelings of compassion, guilt, disgust, and indignation all serve moral functions, directing attention toward situations requiring response. Emotional numbing therefore represents moral incapacitation, not sophistication.

Studies on witnessing demonstrate its importance beyond direct intervention. When people observe suffering without looking away, the suffering becomes socially acknowledged rather than occurring in isolation. This witnessing creates social pressure for change and validates victims' experiences. Refusing to witness is itself political act supporting status quo.

Yet responsibility to feel does not mean carrying weight of entire world. Research on sustainable activism shows that effective engagement requires boundaries, rest, and community. Burnout serves no one. The point is not perpetual distress but maintaining emotional connection to reality rather than retreating into comfortable illusions.

This responsibility extends to recognising one's own suffering alongside others'. Self-compassion research demonstrates that people able to offer themselves kindness prove better able to extend compassion outward. Neglecting personal suffering whilst attending to others' creates unsustainable dynamic producing resentment or collapse.

The courage to care does not promise comfort. It promises contact with reality, with others' humanity and one's own. It reconnects people with meaning not as abstract concept but as lived experience of being present with another conscious life navigating existence's difficulties.

Beyond optimism and pessimism

Caring after disillusionment requires transcending both optimism and pessimism. Optimism denies difficulty whilst pessimism denies possibility. Both represent forms of certainty that caring does not require.

Research on realistic hope demonstrates that sustainable engagement comes not from believing everything will improve but from commitment to values regardless of outcome certainty. Studies show that people maintaining hope despite knowing odds often achieve more than those paralysed by either blind faith or fatalistic resignation.

This stance accepts uncertainty as fundamental condition. The future remains genuinely unknown. Systems prove simultaneously more resilient and more fragile than they appear. Small actions sometimes cascade unpredictably; massive efforts sometimes vanish without trace. Accepting this uncertainty liberates action from needing guaranteed results.

Research on intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation shows that actions pursued for their inherent value prove more sustainable than those dependent on external outcomes. Caring because it aligns with one's values, not because it guarantees success, creates resilience against inevitable setbacks.

Studies on post-traumatic growth reveal that people who maintain meaning and purpose despite trauma often develop greater psychological strength than those never tested. The challenge is not avoiding difficulty but finding ways to remain human within it. Caring provides this pathway.

This perspective acknowledges systems' power whilst refusing to grant them inevitability. History demonstrates that structures appearing permanent collapse, movements dismissed as impossible succeed, and individuals previously voiceless change societies. Yet history equally shows movements failing, hopes disappointed, and suffering continuing.

What caring offers is not certainty but meaning. It provides way to inhabit uncertainty without paralysis, to acknowledge difficulty without surrender, to act without guarantees. In world where control operates through either false promises or manufactured despair, realistic care represents third option.

Connection to previous chapters

This final chapter addresses what follows after understanding mechanisms examined throughout this book. Every previous chapter revealed systems shaping consciousness, behaviour, and belief. This chapter asks what happens after seeing those systems clearly.

Consciousness (Chapter 2): Awareness includes capacity for compassion. The burden of consciousness means feeling not only personal suffering but recognising others' suffering as equally real. Caring honours consciousness itself.

Masks (Chapter 3): Vulnerability requires removing protective masks. Authentic caring cannot occur through persona but only when people risk revealing themselves genuinely. Cynicism is itself mask protecting wounded capacity for connection.

Crowds (Chapter 4): Compassion can spread through populations like other emotions. Collective caring creates social movements whilst collective indifference enables atrocities. The emotional field we contribute to shapes collective outcomes.

Indoctrination (Chapter 5): Caring beyond ideology requires questioning which compassion systems permit and which they forbid. Ideologies often direct empathy toward allies whilst legitimising cruelty toward enemies.

Early belief systems (Chapter 6): Religious ethics emphasise compassion across traditions. Whilst institutions often betray these teachings, the emphasis on caring for strangers, enemies, and vulnerable persists as moral foundation.

Capitalism (Chapter 7): Economic systems commodify care, professionalising compassion whilst devaluing unpaid caring labour. Maintaining non-transactional caring resists reduction of all relationships to exchange value.

Hypernormalisation (Chapter 8): Cynicism represents response to recognising systematic absurdity. Yet refusing to care because systems appear unchangeable surrenders to hypernormalisation's core mechanism: accepting impossibility of alternatives.

Control without violence (Chapter 9): Disciplinary power operates partly through training people not to care. Emotional numbing makes populations manageable. Choosing to remain emotionally responsive represents resistance.

Identity as weapon (Chapter 10): Tribal caring limits compassion to in-groups whilst justifying indifference or hostility toward out-groups. Caring beyond identity categories undermines this weaponisation.

Mental health (Chapter 11): Compassion fatigue, emotional numbing, and cynicism all represent mental health challenges. Sustainable caring requires attending to one's own psychological wellbeing alongside caring for others.

Education (Chapter 12): Educational systems often train compliance by teaching when caring is appropriate and when indifference is required. Maintaining authentic compassion despite this conditioning represents recovered autonomy.

Radicalisation (Chapter 13): Extremism provides certainty about who deserves care and who deserves harm. Resisting this binary whilst maintaining moral clarity requires nuanced compassion acknowledging complexity.

Individuality (Chapter 14): Independent thinking includes capacity to care despite social pressure toward indifference. Herd immunity to caring requires deliberate cultivation of compassion as individual practice.

Secular sacred (Chapter 15): Caring honours consciousness as sacred regardless of metaphysical beliefs. Recognising suffering matters because conscious beings experience it creates ethical foundation transcending ideology.

Algorithmic mind (Chapter 16): Digital platforms engineer emotional responses whilst often promoting outrage over compassion. Maintaining genuine caring requires resisting algorithmic manipulation of emotional life.

Economy of attention (Chapter 17): Caring requires attention sustainable over time. Fragmented attention produces compassion fatigue. Protecting attentional capacity enables sustained engagement with others' wellbeing.

Story controls mind (Chapter 18): Narratives shape compassion by determining whose suffering counts. Questioning dominant stories whilst remaining emotionally engaged requires critical consciousness that does not default to cynicism.

Body remembers (Chapter 19): Compassion is embodied experience, not abstract concept. Feeling others' pain physiologically whilst maintaining regulated nervous system enables sustainable caring without overwhelm.

Conclusion: the possibility of care

This final chapter has examined what remains after understanding how consciousness is shaped, behaviour manipulated, and belief constructed. It has documented why cynicism represents incomplete liberation, what research reveals about compassion and vulnerability, how caring survives knowledge of systemic failure, and why maintaining capacity for genuine concern represents crucial resistance.

The opening scenario of scrolling past suffering whilst feeling nothing illustrates compassion fatigue operating practically. Constant exposure to atrocity produces adaptive numbing. Yet this protection exacts costs: isolation, meaninglessness, disconnection from reality and from oneself.

Research demonstrates that cynicism, whilst appearing sophisticated, produces worse outcomes across health, relationships, and wellbeing. Studies show cynical individuals experience elevated stress, reduced life satisfaction, and become trapped in self-fulfilling prophecies where expecting the worst produces behaviour generating evidence confirming cynical worldview.

Compassion fatigue represents real phenomenon requiring attention. Healthcare workers, activists, and anyone sustained exposure to suffering risk depletion. Yet research also shows that compassion proves more sustainable than empathic distress alone. Caring combined with appropriate boundaries and effective action prevents burnout better than emotional suppression.

The science of compassion reveals it as trainable capacity with measurable neural correlates. Loving-kindness meditation increases positive emotions, social connection, and physiological resilience. Importantly, compassion does not require naïveté but actually proves more effective when grounded in clear perception of difficulty.

In-group bias demonstrates that human compassion typically operates within boundaries. Brain imaging shows automatic favouritism toward perceived in-group members. Yet moral circles can expand through perspective-taking, cross-group relationships, and narratives highlighting common humanity. Caring beyond tribe represents conscious choice resisting automatic bias.

Vulnerability research challenges assumptions equating openness with weakness. Studies show that willingness to be seen, admit uncertainty, and express genuine emotion creates authentic connection whilst invulnerability produces isolation. Choosing vulnerability whilst aware of risk requires strength unavailable to those armoured against feeling.

The responsibility to feel emerges from awareness. Once systemic harm becomes visible, claiming ignorance becomes impossible. Feeling itself becomes moral act: maintaining emotional connection to reality rather than numbing. Research shows that witnessing suffering, even without direct intervention, serves moral function by acknowledging what occurred.

Caring transcends both optimism and pessimism. Studies on realistic hope show that commitment to values regardless of outcome certainty sustains engagement better than either blind faith or fatalistic resignation. Intrinsic motivation proves more resilient than dependence on guaranteed success.

This book has traced mechanisms through which consciousness is managed, behaviour directed, and belief constructed. It has shown how crowds form, how indoctrination operates, how capitalism extracts, how control functions without violence, how identity weaponises, how mental health pathologises, how education disciplines, how radicalisation captures, how individuality erodes.

It has examined how hypernormalisation manufactures acceptance, how algorithms exploit attention, how attention itself becomes commodified, how language shapes thought, and how bodies encode experience beyond conscious access. Each chapter revealed forces shaping human experience whilst appearing natural or inevitable.

Yet understanding these mechanisms does not require abandoning care. The opposite proves true: seeing clearly how systems operate makes caring more essential, not less. Cynicism represents surrender disguised as sophistication. Maintaining capacity for genuine concern whilst understanding manipulation represents matured consciousness.

What makes caring after disillusionment especially significant is that it cannot be exploited through false promises. Naïve compassion believes suffering resolves easily. Mature compassion acknowledges complexity, systematic resistance to change, and human capacity for self-deception including one's own. It cares anyway.

This caring does not guarantee outcomes. Systems prove remarkably resilient. Individual actions often disappear without observable impact. Suffering persists despite efforts to alleviate it. Yet the question is not whether caring succeeds but whether it represents how one chooses to inhabit consciousness.

The secular sacred framework recognises that consciousness itself matters because it can suffer. Ethical commitments flow from acknowledging that pain feels genuinely painful to those experiencing it, that joy feels genuinely joyful, that meaning matters to those who create it. This grounds care in reality rather than ideology.

Whether individuals and societies can maintain caring whilst systems engineer indifference remains uncertain. Forces promoting cynicism, emotional numbing, and tribal hatred are powerful and often invisible. Digital platforms optimise for outrage over compassion. Economic structures reward exploitation over care. Political systems weaponise identity whilst demanding loyalty.

Yet history demonstrates that caring persists despite systems attempting to eliminate it. People continue helping strangers, protecting vulnerable populations, resisting injustice, maintaining humanity in inhumane conditions. This persistence suggests that capacity for care represents something fundamental rather than ideological overlay.

In world where control operates increasingly through managing emotional life, choosing to feel represents resistance. Not indulgent emotionality but attentive presence. Not naive optimism but commitment to remaining open despite knowing danger. Not certainty about outcomes but willingness to act from values regardless.

The courage to care after understanding manipulation, after recognising systematic exploitation, after seeing how belief operates, represents perhaps the most profound form of freedom available. It is freedom not from knowledge but through it. Freedom not as absence of constraint but as conscious choice about how to meet constraint.

This caring offers no guarantees. It does not promise that systems will change, that suffering will end, or that justice will prevail. What it offers is way to inhabit existence that honours consciousness itself: recognising that what happens to others matters because they experience it, that one's own experience matters in same way, that this mutual vulnerability creates ethical responsibility.

The question facing anyone who understands how control operates is not whether to care but how to care sustainably, how to maintain emotional responsiveness without overwhelm, how to act without guarantees, how to remain human whilst systems incentivise becoming machine.

In the end, caring is not strategy for changing world but way of being in it. It does not depend on believing change is possible or impossible. It simply recognises that consciousness experiences suffering and joy, that this experience matters, and that responding to it with attention rather than indifference represents fundamental choice available to aware beings.

This book began without expectation that world makes sense. It ends without providing sense world lacks. What it offers instead is observation: that systems shape experience systematically, that understanding these systems changes nothing and everything, and that caring after understanding represents not naïveté recovered but wisdom earned.

The courage to care, finally, is courage to remain conscious fully. Not consciousness as burden alone but as capacity including awareness, perception, feeling, and choice. To care is to honour consciousness by refusing to numb it, to instrumentalise it, or to surrender it to forces demanding compliance.

Whether this proves sufficient remains unknown. What is certain is that indifference guarantees nothing changes. Caring guarantees nothing either. But it guarantees it differently. It creates space where change becomes possible not through certainty but through commitment to remaining present with what is whilst imagining what might be.

As I see it, this is where responsibility ultimately lives: not in belief, not in obedience, but in willingness to remain human when it would be easier not to be. To feel when numbness offers protection. To care when cynicism appears wise. To stay present when withdrawal seems rational. This is not optimism. This is choice.

End of Chapter 20