Mozambique’s Quiet Giant: When Energy Becomes the New Gold

Gold glints, but power pulses. In Southern Africa, something monumental is taking shape on the Zambezi River. Mozambique’s $5–6 billion Mphanda Nkuwa Dam, expected to deliver 1,500 megawatts of electricity by 2031, is more than an engineering marvel. It is a declaration that in the twenty-first century, energy—not gold, not oil, not even the dollar—has become the true currency of sovereignty.

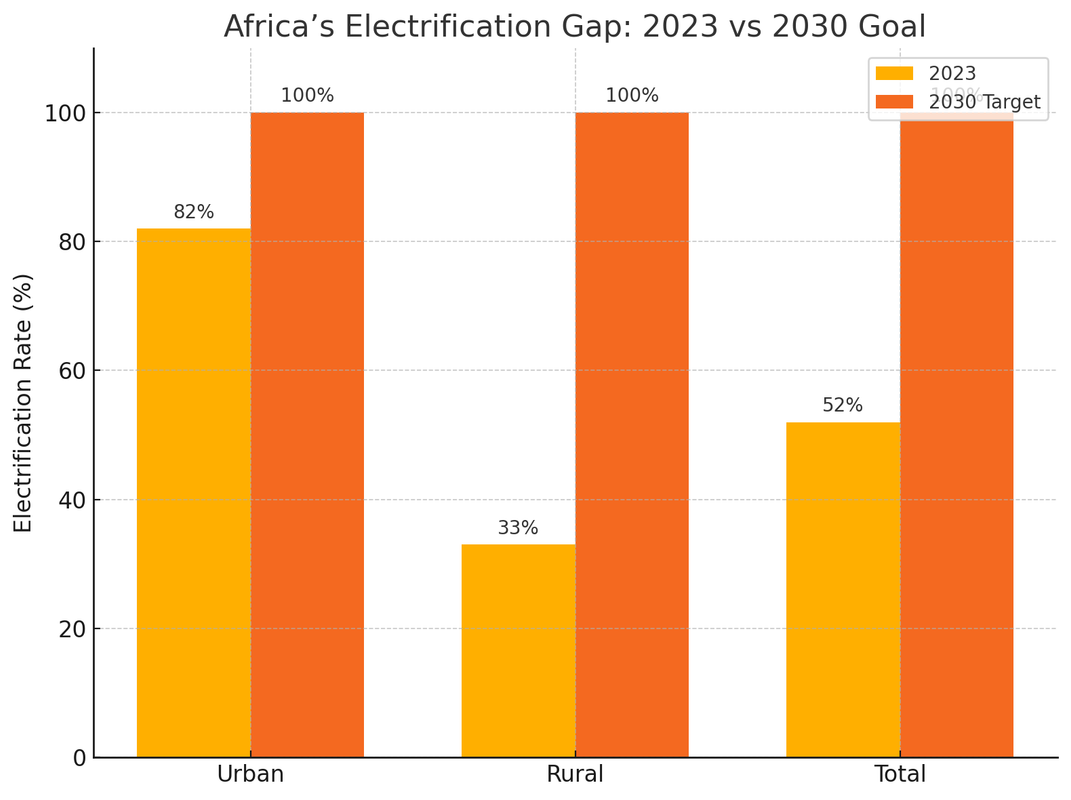

Sub-Saharan Africa remains the world’s most energy-poor region, home to 85 percent of those living without electricity. In Mozambique itself, however, access is expanding rapidly. In 2018, only 31 percent of the population had power; by 2024, that figure had nearly doubled to 60 percent. The government connected more than half a million homes last year and aims to reach another 600,000 in the next twelve months. Yet the gap between progress and promise remains vast. Across Africa, 82 percent of urban residents enjoy electricity, but in rural areas, the figure plunges to 33 percent. To achieve universal access by 2030, the continent must more than triple its historical pace of grid expansion.

The Mphanda Nkuwa Dam is Mozambique’s bold attempt to close this gap while turning itself into an exporter of power. Located sixty kilometers downstream from the existing Cahora Bassa Dam, the new project will stretch across ninety-seven square kilometers, with a wall rising 103 meters high. Four turbines, each producing 375 megawatts, will together generate an estimated 8,600 gigawatt-hours annually. Financing has been cobbled together through a 70/30 split between a consortium—featuring EDF, TotalEnergies, Sumitomo, and Kansai Electric—and Mozambique’s own utilities, EDM and HCB. The European Union and the European Investment Bank have already pledged more than €500 million for construction and transmission. For Southern Africa, this is the largest hydro investment in half a century, designed to help fill a regional energy deficit of nearly 10,000 megawatts.

Mozambique is unusually well-positioned to play this role. Its theoretical energy reserve of 187,000 megawatts is the largest in the Southern African Power Pool, yet its operating capacity in 2018 was barely 2,300. Hydropower already accounts for nearly all of its production, thanks to the Cahora Bassa facility, which alone generates more than 2,000 megawatts and exports two-thirds of that output to South Africa through a 1,400-kilometer transmission line. Smaller projects are coming online as well: the $750 million Temane gas-fired plant, which will add 450 megawatts, and a series of mini-hydro plants financed through the GET FiT scheme that, while modest—adding 4 to 15 megawatts each—still supply power to hundreds of thousands of people annually.

The broader African context underscores why Mozambique’s gamble matters. The World Bank and African Development Bank are spearheading “Mission 300,” an initiative to bring electricity to 300 million Africans by 2030, with $90 billion in pledged support. Yet Africa still attracts just 2 percent of global renewable investment, despite holding enormous potential in rivers, sun, and wind. The African Renewable Power Alliance aims to quintuple the continent’s renewable capacity, from 67 gigawatts in 2024 to 300 by the end of the decade. Reaching universal electrification, however, will require $64 billion in annual investment—more than double current flows.

Against this backdrop, Mphanda Nkuwa carries both promise and peril. On the one hand, it could transform Mozambique into a regional power broker, exporting electricity to neighbors starved of reliable supply. South Africa’s rolling blackouts, Zimbabwe’s fragile grids, and Malawi’s chronic shortages all suggest a ready market. For Mozambique, exporting electricity means not only foreign currency but also geopolitical leverage, the ability to provide or withhold the power that keeps hospitals lit and factories running.

On the other hand, the risks are formidable. Mozambique’s public debt already stands at $17 billion, with $2.1 billion in servicing costs last year alone. Adding a $6 billion dam introduces fresh vulnerability. Climate change compounds the uncertainty: hydropower depends on consistent river flow, but droughts are growing more frequent across the region. Social costs are also unavoidable. The reservoir will displace around 1,400 families, while more than 200,000 downstream livelihoods tied to irrigation and fisheries could be disrupted. In short, Mphanda Nkuwa could become a vault of sovereign wealth—or a stranded asset.

Yet Mozambique’s dam is not unique—it is part of a continental wave of “dam geopolitics.” Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam (GERD), costing $5 billion, has already begun reshaping the Nile Basin. With a planned capacity of 6,450 megawatts, GERD aims to make Ethiopia the electricity hub of East Africa, exporting power to Sudan, Kenya, and beyond. But the project has provoked fierce opposition from Egypt, which fears that the dam will choke the Nile’s downstream flow. GERD demonstrates that large dams are not simply development projects; they are geopolitical levers, capable of triggering diplomatic standoffs and reshuffling regional power hierarchies.

Further west lies the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Inga scheme, often dubbed the “crown jewel” of Africa’s hydropower dreams. The Inga I and II dams, built in the 1970s and 1980s, generate around 1,700 megawatts, but the site’s potential dwarfs even Ethiopia’s GERD. Plans for “Grand Inga,” with a projected capacity exceeding 40,000 megawatts, could theoretically power most of Africa. Yet political instability, financing gaps, and governance failures have kept the project stalled for decades. Inga symbolizes both Africa’s immense energy potential and the chronic obstacles that prevent its realization.

Seen in this context, Mozambique’s Mphanda Nkuwa is less a solitary gamble than a chapter in Africa’s broader bid to turn rivers into sovereignty. Like Ethiopia, Mozambique hopes to translate hydropower into regional clout. Unlike Congo, it has secured credible international backing and a relatively modest scale, making success more plausible. Yet the risks—of debt, climate variability, and social upheaval—echo across all three projects.

The symbolism, though, is unmistakable. Gold has always derived its power from trust and scarcity. Hydropower offers a different kind of trust: the steady hum of turbines turning water into reliable kilowatts. For a modern economy, that reliability is wealth more tangible than bullion. In the twentieth century, nations measured prosperity by their oilfields and mines. In the twenty-first, they may measure it by the gigawatts they can generate and trade.

While pundits obsess over the fate of the dollar or the latest spike in gold, Mozambique is quietly rewriting the standard. If Mphanda Nkuwa delivers as promised, Mozambique will not just light up its own cities but recast itself as a broker of Southern Africa’s stability. In doing so, it will demonstrate a new truth: sovereignty in the modern world is not secured by vaults of gold but by control of the grid.

Add comment

Comments