Mauritius: The Exporter Who Imports Hunger

The Island of Plenty That Starves

Mauritius is celebrated in development textbooks as an African miracle, a small island nation that supposedly cracked the code of prosperity by moving from sugarcane monoculture to a diversified economy of tourism, textiles, and offshore finance. But behind the glossy brochures and IMF commendations, lies a paradox so bitter that it borders on satire: an exporter of food products that imports hunger for its own people.

This is not a mere quirk of global trade. It is a structural reality rooted in colonial land ownership, post-independence political bargains, and a present-day elite unwilling to dismantle the model that enriches them.

Mauritius cultivates vast tracts of fertile land, yet a disproportionate share is reserved for sugarcane, rum, and exports destined for wealthier markets. Meanwhile, supermarket shelves are lined with imported rice, wheat, lentils, oil, onions, potatoes, canned tuna, and even fruits that could be grown locally. Food insecurity grows sharper with every price spike, leaving the ordinary Mauritian household paying more for less.

The cruel irony is that the very tuna hauled by Mauritian fleets from the Indian Ocean is shipped frozen to Japan and Europe to be served as sashimi, only to return in the form of imported cans, priced out of reach for many Mauritians. Hunger is not the absence of food. It is the result of policy.

Colonial Seeds

The roots of this paradox stretch back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when colonial authorities institutionalised a plantation system based on monoculture. Sugar became both cash crop and shackle. Land grants favoured Franco-Mauritian families who entrenched themselves as the island’s ruling economic class.

When independence came in 1968, the new state did not dismantle this system; it merely nationalised its dependence. The ruling elite struck a bargain with the sugar barons: political stability for economic continuity. Land reform was avoided, plantations remained intact, and successive governments used sugar export revenues to bankroll welfare schemes.

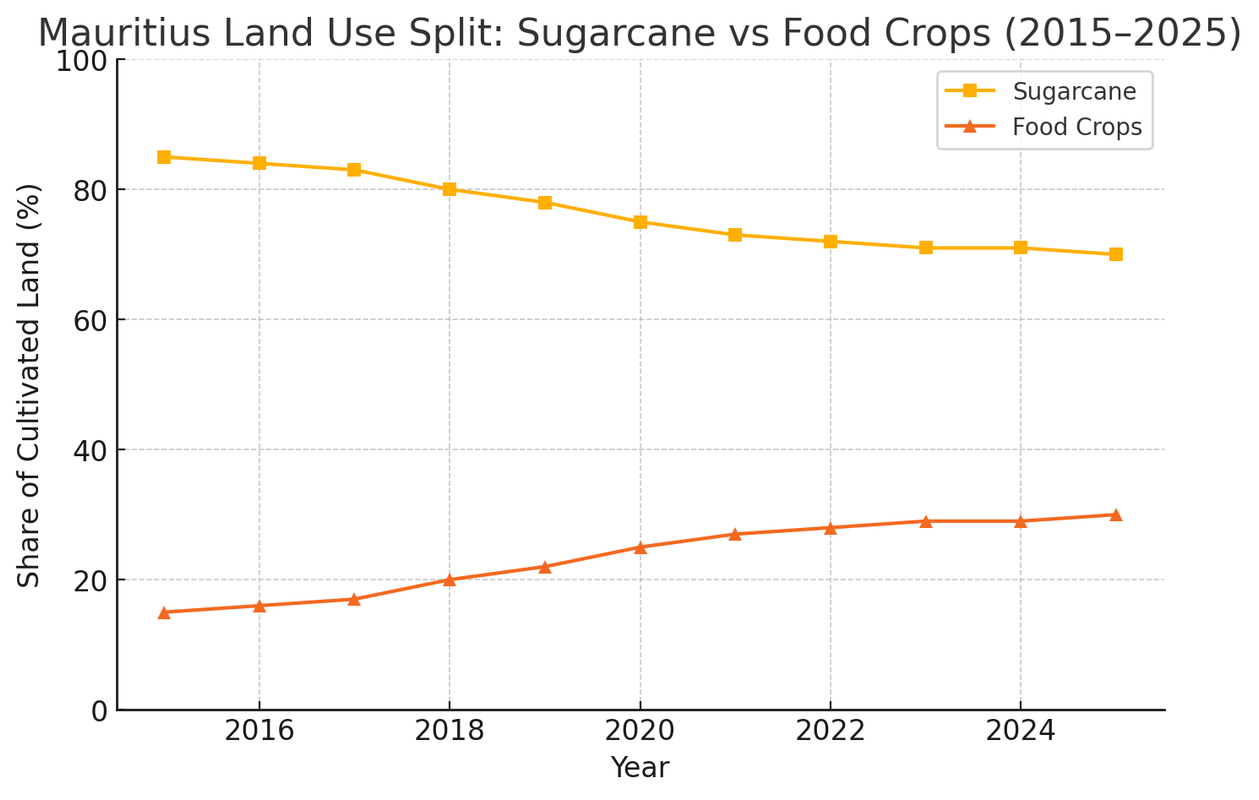

But the land question never went away. By the 2000s, only a fraction of arable land was dedicated to vegetables or staples. Food sovereignty was traded for export earnings.

Import Dependency

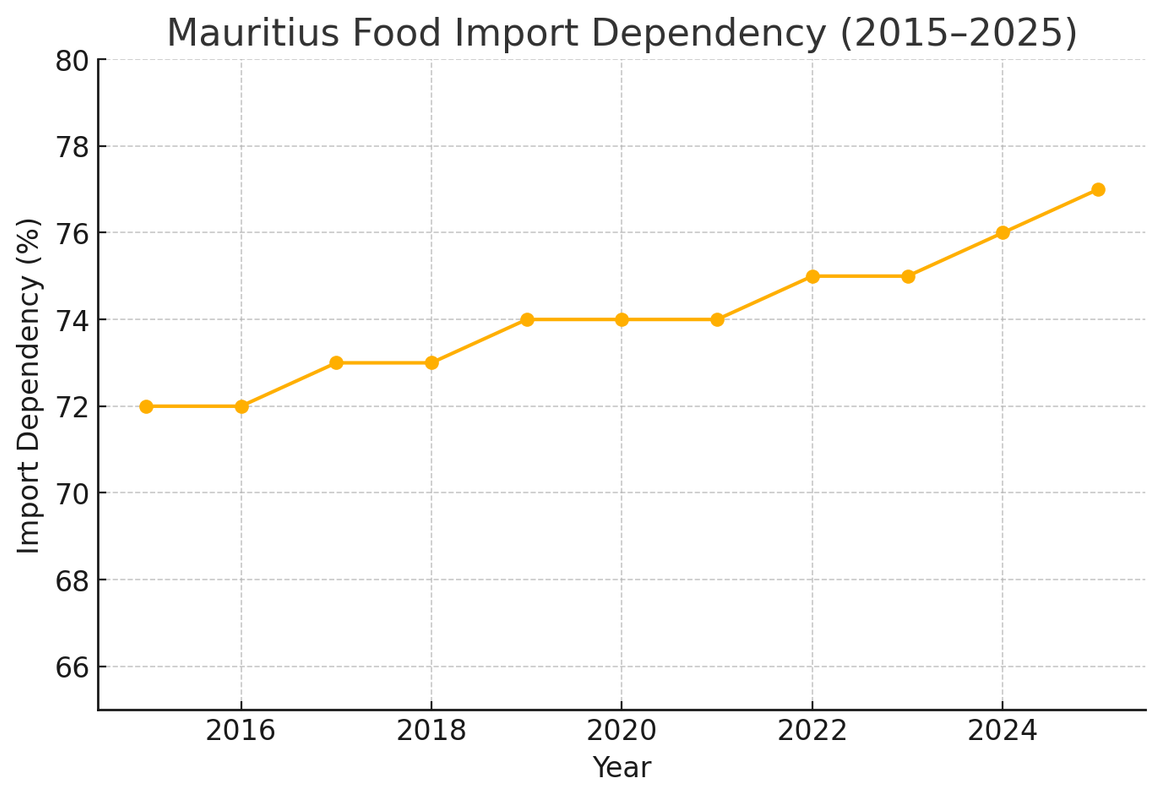

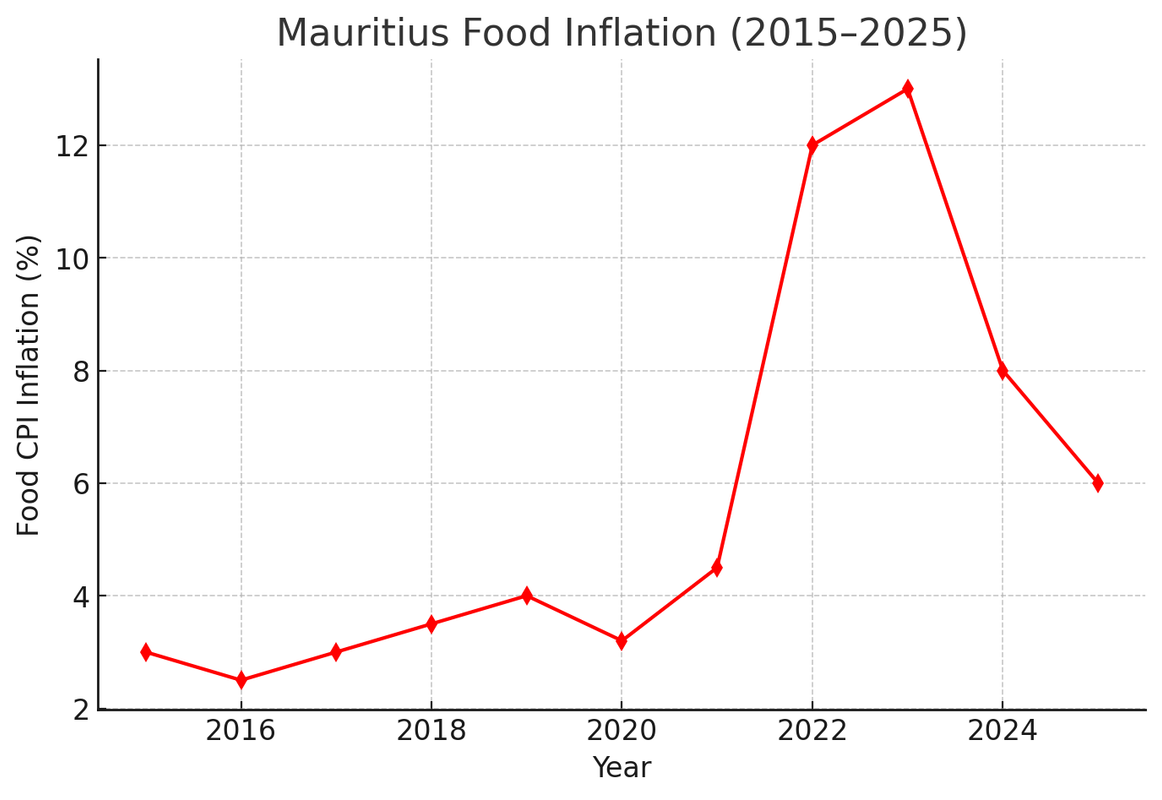

Charts of Mauritius’ food trade tell the story with brutal clarity. Between 2015 and 2025, food import dependency rose steadily, crossing 70 percent in some categories. Inflation in global commodity markets translated into double-digit spikes in local supermarket prices.

Households reported cutting back on proteins, substituting fresh produce with cheaper imported carbohydrates. The “basket of survival” shifted away from nutrition toward caloric endurance.

Paradoxically, Mauritius exported premium-grade seafood and specialty sugars at the same time. The domestic population was left to compete for low-quality imports at high prices.

The Politics of Hunger

Why would any government allow such a system to persist? The answer lies in the logic of political patronage. Food imports are not neutral; they are lucrative conduits of power. Import licenses, shipping contracts, and distribution rights are concentrated among politically connected intermediaries.

Rice, oil, and wheat are imported in bulk through a handful of state agencies and private cartels. Margins accumulate in the pockets of a small elite. Any serious attempt to reduce import dependency would threaten this patronage network.

Instead, successive governments stage-manage hunger. They announce subsidies on “basic commodities” during election years, temporarily soothing discontent while leaving the structural dependency intact. Hunger thus becomes both a managed crisis and a political instrument.

The Tuna Paradox

The story of tuna captures Mauritius’ hunger paradox in cinematic detail. Every day, fleets unload thousands of tonnes of yellowfin and skipjack tuna at Port Louis. Much of this is destined for processing plants that export directly to the EU and Japan.

At the docks, the fish are transformed into frozen loins, fillets, and sashimi-grade slices. A smaller fraction is canned for international brands — some owned by Thai and European conglomerates. The final products end up in London supermarkets, Tokyo sushi bars, or Paris bistros.

Mauritians, meanwhile, must buy back the same tuna in cans priced higher than imported mackerel. For many, it is simply unaffordable. The very fish that sustains Mauritian exports has become a luxury in Mauritian kitchens.

Droughts, Climate, and the Mirage of Self-Sufficiency

Climate change adds another cruel layer. Rainfall patterns have grown erratic, with extended droughts cutting into local vegetable production. Farmers complain of water rationing while golf courses and luxury hotels remain lush and green.

Government strategies routinely promise “food self-sufficiency,” but targets are missed with ritual consistency. Instead of diversifying production, land continues to be converted into real estate projects, luxury villas, and smart cities. The fertile topsoil of Mauritius is being paved over in the name of development.

Analysis: Economics of Dependency

Charts comparing land use between sugarcane and food crops show the imbalance starkly. More than half of arable land remains under sugar, while food crops stagnate in single digits.

Food inflation has outpaced general inflation almost every year between 2015 and 2025. The poorest 40 percent of households spend more than a third of their income on food. Dependency ratios reveal that Mauritius is among the most food-import dependent countries in Africa, despite having land and capacity for greater self-reliance.

In effect, the economy has been structured to guarantee dependency. International financial institutions applauded Mauritius for liberalising trade and boosting exports, but the human cost is visible in every grocery bill.

The Psychology of Gratitude

Governments have perfected a narrative of scarcity and relief. Citizens are reminded that “we are a small island with no resources,” as if food sovereignty were a geological impossibility. Subsidies are marketed as generosity, rather than a partial refund on a rigged system.

In this theatre, hunger is rebranded as resilience. Mauritians are told to be grateful that their government “protects” them with targeted subsidies, even as the same state enables the structures that cause inflation in the first place.

Exporting Mirage, Importing Hunger

The miracle story of Mauritius was always a mirage. Prosperity was measured in GDP growth, FDI inflows, and export receipts. Nowhere in the equation was the basic dignity of food security.

Hunger in Mauritius is not about scarcity; it is about priority. Land, water, and policy have been dedicated to serving external markets and entrenched elites. The Mauritian citizen, once promised a share of the nation’s progress, has been relegated to the supermarket aisle, queuing for imported onions and overpriced tuna cans.

Breaking the Cycle

The path forward is not utopian. Mauritius could diversify crops, reduce sugarcane acreage, invest in agro-ecology, and reorient subsidies toward local food production. It could reform import licensing to break cartels, ensuring fairer access to basic goods.

But such steps would require dismantling entrenched interests. They would demand political courage of a kind absent in Mauritius for decades.

Until then, Mauritius will remain the island that feeds others while importing hunger for its own.

Notes & Methodology

This article draws on data from Mauritius’ Statistics Office, FAO trade reports, IMF Article IV consultations, and the Truth and Justice Commission’s findings on land dispossession. Inflation and dependency trends are based on publicly available statistics from 2015–2025. Qualitative insights are supported by interviews with small farmers, trade unionists, and comparative political economy literature.

Add comment

Comments

Your ANALYSIS IS SOUNDLY RESEARCHED AND IS THOUGHT PROVOKING...?

THOSE REMARKS LEAD ME TO CONCLUDE THAT OUR ECONOMY NEEDS TO DEMOCRATISE N THIS SITTING GOVERMMEMT GOVERNMENT IS NOT COMMITTED TO CHANGE A IOTA THE ECONOMIC LANDSCAPE THAT IS THERE SINCE 1968. WE NEED A NEW CONSTITUTION 2.0 WITH A NEW VISION N A NEW TEAM.!!!